|

| Christine Osborne/CORBIS |

|

| Araldo de Luca/CORBIS |

An Example from the Life of Abraham. Abraham, for instance, kept several concubines—Genesis 25:6, and had sons by them—but none gave him great deal of complication than Sarah's Egyptian maidservant named Hagar. The first snag that this arrangement is liable to promote is between wife and mistress. Hagar was an Egyptian maidservant who was dragged into the mess spilled by Abraham and Sarah when they attempted to facilitate God’s promise of a son and heir (Genesis 15:40). Knowing the fact that their bodies were “as good as dead” (Romans 4:19), they resorted to the custom of impregnating the Sarah’s slave (Genesis 16:3). And out of that arrangement, Hagar bore Ishmael; a development that changed the attitudes of both Hagar and Sarah toward each other. The fourth verse in Genesis 16 says that Hagar began to despise her mistress. Sarah, armed with her legitimate right as wife and Hagar’s owner, coupled with an embittered soul, it was easy for her to mistreat her and send the slave running away (verse 6). But in a desert road, God meets Hagar and tells her to “go back to [her] mistress and submit to her” (verse 9), with a promise. On account of the respect God had for Abraham, He assured to greatly increase the progeny of Abraham from her body “that they will be too numerous to count” (verse 10).

|

| Bettmann/CORBIS |

Hagar did as the Lord commanded and returned to Sarah. She gave birth to Ishmael while she stayed with her mistress (verse 16). Little more than a decade later, Sarah got pregnant and gave birth to the awaited heir, Isaac (21:1-5). At this point, Sarah compelled Abraham to divorce Hagar and disinherit Ishmael by sending her away (Genesis 21:10). The matter, according to the Scriptures, “distressed Abraham greatly” (verse 11).

An Example from the Life of Jacob. It distressed the patriarch greatly “because it concerned his son” (Ibid.). One observable problem in ancient concubinage is seen in the conflict among the offspring. In Genesis 21:8 to 10, the sight of Ishmael teasing Isaac infuriated Sarah prompting her to banish the servant child and her mother. And that ended a sibling conflict which could have grown worse in time, such as what happened among Jacob’s eleven sons when their jealousy of Joseph sent him into Egyptian bondage. The passage in Genesis 35:23 to 26 outlines Jacob’s family. In order of marriage, Leah was the first; and from this union brought Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Judah, Issachar, and Zebulun. From Leah also came Dinah, Jacob’s only daughter (30:21). Rachel, though Jacob loved her first, fell second to give him Joseph and Benjamin. By her maidservant Bilhah came Dan and Naphtali. Leah, too, offered her maidservant Zilpah and from her came Gad and Asher.

Examples from the Life of the Israelite Kings

The first three Israelite kings were not from this contingent. King Saul was known to have kept a wife and a concubine, a fact we either know little or care little about. Saul’s wife was Ahinoam (1 Samuel 14:50), from whom came Jonathan, Ish-Bosheth (who went by the names Ishvi, Esh-Baal, and possibly Abinadab, 31:2), and Malki-Shua (verse 49); and the daughters Merab and Michal, the princess whom Saul gave to David as wife at the cost of two hundred Philistine foreskins (1 Samuel 18:27). The concubine was Rizpah (2 Samuel 3:7,21:8,10,11).While the trouble that the women entangled in concubinage could churn out is well established in the consciousness of the Israelite, Saul’s disobedience had instead created for his partners the lifelong pain of losing their sons in tragic deaths that could have well been avoided from the start. We have already known how in 1 Samuel 31, Ahinoam lost her three sons in a battle against the Philistines on Mount Gilboa. Rizpah lost her two sons, Armoni and Mephibosheth (2 Samuel 21:8), to the Gibeonites who had them immolated for a mandate defied by—you guessed it—Saul.

Rizpah, Saul's Concubine, in the Middle of Saul's Transgression with the Gibeonites

The first three Israelite kings were not from this contingent. King Saul was known to have kept a wife and a concubine, a fact we either know little or care little about. Saul’s wife was Ahinoam (1 Samuel 14:50), from whom came Jonathan, Ish-Bosheth (who went by the names Ishvi, Esh-Baal, and possibly Abinadab, 31:2), and Malki-Shua (verse 49); and the daughters Merab and Michal, the princess whom Saul gave to David as wife at the cost of two hundred Philistine foreskins (1 Samuel 18:27). The concubine was Rizpah (2 Samuel 3:7,21:8,10,11).While the trouble that the women entangled in concubinage could churn out is well established in the consciousness of the Israelite, Saul’s disobedience had instead created for his partners the lifelong pain of losing their sons in tragic deaths that could have well been avoided from the start. We have already known how in 1 Samuel 31, Ahinoam lost her three sons in a battle against the Philistines on Mount Gilboa. Rizpah lost her two sons, Armoni and Mephibosheth (2 Samuel 21:8), to the Gibeonites who had them immolated for a mandate defied by—you guessed it—Saul.

Rizpah, Saul's Concubine, in the Middle of Saul's Transgression with the Gibeonites

The story in 2 Samuel 21:1 to 14 tells that Saul, “in his zeal of Israel and Judah” (verse 2) attempted to do what Joshua centuries before him would not: “annihilate the Gibeonites.”

|

| George Steinmetz/CORBIS |

The Gibeonites, according to 2 Samuel 21:2, were an ancient race of Amorites who, in Joshua 9, extracted Israelite protection through a cunning ruse. In verses 4 to 6 and 9 to 14, they successfully deceived the Israelites into believing that they were worn and vulnerable travelers from some far distant land drawn to where the Israelites were “because of the fame of the Lord” (verse 9). Flattered it seemed by the testimony posed by the Gibeonites that Joshua and the Israelites forgot the fundamental procedure of inquiring of the Lord (verses 14 and 15) and on went the decision to establish a treaty of peace with these people , unwittingly disobeying God’s mandate never to make any covenant with them (Exodus 23:32).

|

| Adrian Abib/CORBIS |

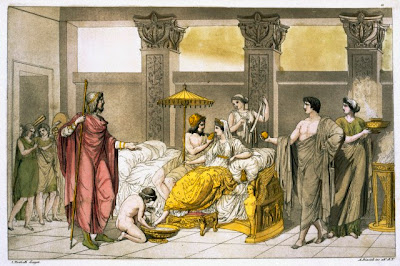

The sanctity of their survival sealed by an oath invoking the Name of the Lord demanded the lives of seven of Saul’s male descendants with their bodies left unburied and exposed “before the Lord” (verse 6). David had five sons of Saul’s daughter Merab, along with the two sons of Rizpah, delivered to the Gibeonites and immolated (2 Samuel 21:8 to 9). When the Gibeonites were done with them, Rizpah came and stood by the bodies of her two sons, spread sackcloth on a rock, and, enduring night and day and the pouring rain, scared away scavenging birds and other wild animals that tried to approach the corpses. This prompted King David to have the remains of Rizpah and Merab’s sons gathered and given a proper burial. Along with this, he claimed from the people of Jabesh Gilead the bones of Saul and Jonathan and buried them in the tomb of Saul’s father Kish in Benjamin (verses 12 to 14).

|

| Werner Forman/Corbis |

Her name appears four times in the Bible. In 2 Samuel 3:7, her name gets dragged into a scandal cooked up by Ish-Bosheth in an attempt to derail the growing influence exerted by Abner, the king’s general and uncle, in their clan. As we already know, King Saul by this time was already unfit to rule. His obsession to murder David through the influence of intermittent demonic oppression and possession and the Prophet Samuel’s public declaration that God had rejected him as king (1 Samuel 15:23,26,28) were factors enough for many to seek other leaders in place of Saul. One of these was David. Another was Abner, at least in Ish-Bosheth’s interpretation of how Abner had been flexing his influence in Saul’s clan. It could have been that Abner had been trying to gain the clan’s support to install him as king and thereby keep the supremacy over all Israel. Ish-Bosheth’s scandalous accusation, however, may have irredeemably shattered Abner’s delicate prospects to gain the major trust of the clan, so he opts for the next best thing: a defection over to David’s side.

Saul was a normal reflection of his society as he escaped the technicality of taking “many wives” (Deuteronomy 17:17). He had one wife and one other wife, and that was it. But how many is “many”? When God transferred the anointing as king, He was risking landing it on someone who had a starkly illicit control over his raging hormones.

|

| Jim Zuckerman/Corbis |

David's Life with his Wives

As we read of David’s story, we can notice that the stages of his life were landmarked by the women he loved. Michal, King Saul’s princess, would cover David’s early rise to popularity; Abigail would be during the stage when he was eluding Saul’s murderous pursuit; Bathsheba, who would mark the zenith of David’s life as by then the undisputed king of Israel; and Abishag, a Shunammite girl given to him by his servants during the twilight years of his life to attend and take care of him (1 Kings 1:2), since by then his senility had robbed him of the ability to basically care for himself (verse 1).

As we read of David’s story, we can notice that the stages of his life were landmarked by the women he loved. Michal, King Saul’s princess, would cover David’s early rise to popularity; Abigail would be during the stage when he was eluding Saul’s murderous pursuit; Bathsheba, who would mark the zenith of David’s life as by then the undisputed king of Israel; and Abishag, a Shunammite girl given to him by his servants during the twilight years of his life to attend and take care of him (1 Kings 1:2), since by then his senility had robbed him of the ability to basically care for himself (verse 1).

The "Abigail Age of David's Life": “This part of my life is called, ‘Running.’ And I wanna thank my wife Abigail for all of the support and prayer; and, of course, God without whose blessing and guidance my head would be stuck at the edge of a royal spear right now!”

But even aside from these ladies, David was known to have married some lesser known wives like Ahinoam of Jezreel (2 Samuel 3:2), Maacah daughter of Talmai king of Geshur (verse 3), Haggith (verse 4), Abital, and Eglah (verse 5). He was also known to have kept a harem of concubines. In 2 Samuel 15:16, he was known to have left ten of them to take care of the palace when he escaped Jerusalem before his usurping son Absalom could take over the city.

"This part of my life is called, ‘Being Stupid’!” It was the day the king came to his rooftop, saw the bathing Bathsheba, and was conquered. But to what price?

The number of the partners David kept was not exactly the direct answer to our question as to how many did Deuteronomy 17:17 mean by “many wives.” After Saul’s death, David’s life changed. The ease, popularity, and prosperity facilitated the growth of his family in a way that he added more wives who bore more children, sadly, beyond his ability to discipline. As a result, the privileged royal lifestyle and the unchecked excesses of unrestraint swelled into a deposit that encrusted their God consciousness, like what led to the chain of events involving Amnon, Tamar, and Absalom (2 Samuel 13). According to the chart provided in 2 Samuel 3:2-5, Amnon, David’s “firstborn” was born of Ahinoam of Jezreel (verse 2); Tamar and Absalom were siblings from Maacah, the Geshurite princess (verse 3).

|

| Mimmo Jodice/CORBIS |

One of the great scandals of David’s life began with his desire for Bathsheba. The lust of a night as he watched the woman bathing turned into fornication, which resulted into her getting pregnant. In his attempt to cover up his blunder, he recalled Bathsheba’s husband Uriah from the battlefield and tried to get him to sleep with her, which even in his most inebriated state would not violate the code of a soldier in a time of battle, which ignites the frustration of the king, which leads him to pen a directive to his general Joab to march Uriah into the part of the battlefield where the fighting is thickest and to abandon him there. Uriah successfully hand-carried the sealed letter to Joab and with great regret, the latter obeys. The battle ended with Uriah as casualty, a victim not of war but of a carefully meditated plot to murder him.

|

| Alinari Archives/CORBIS |

It could be considered, therefore, that the “many” expressed in Deuteronomy 17:17 is the point that goes beyond a man’s ability to control his dependents and keep them from self-destructing. In the example that involved Amnon, Tamar, and Absalom, it presented David’s family self-destructing immorally.

|

| Mimmo Jodice/CORBIS |

Abishag was one described in 1 Kings 1:4 as “very beautiful,” the result of a nationwide search for “a young virgin to attend the king and take care of him,” who “can lie beside him” to keep the king warm (verse 1). The “beauty search” proved to be a great success in Abishag as she was faithful in her task and even maintained her virginity throughout the period she took care and waited on the king (verse 4). If she had ever served a master younger and other than David at another time, that master would call that point of his life, “Being Happy.”

Solomon's Polygamy and its Possible Egyptian Origin

The penchant for the lovely ladies passed on from David to his son Solomon whose fame was built, among others, on the plain fact that he loved “seven hundred wives of royal birth and three hundred concubines” (1 Kings 11:3), maintaining an unbroken violation of God’s condition in Deuteronomy 17:17. Yet if there were any value to virtue in this aspect of his life, it was the fulfillment of the second part of the passage: “…or his heart will be led astray” (Ibid.). And true enough, “his wives led him astray” (1 Kings 11:3).

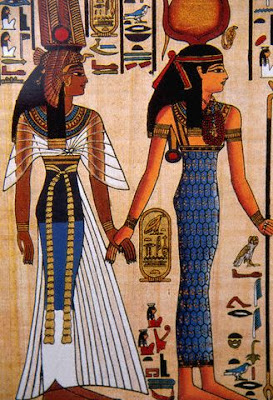

In our recent article, The King After God: All the King's Horses, we have suspected that King Solomon amassed a great number of horses and chariots in emulating the Pharaoh of Egypt, whose collection was renown for its quantity and quality throughout the region. War horses and chariots, however, were not the only array he wanted in his treasure trove. The kings of Egypt were known to have loved multiple wives and concubines. Ramses II, said to be Moses' contemporary, was reported to have kept as many as fifty wives, and from them the famed Nefertari was chosen to become his queen, the chief of all his female consorts. With the record we have available today, we may well say that Solomon surpassed Ramses II in this respect, by a great measure—try lining up fifty against a thousand wives and concubines! One comparable element the Israelite king did not adopt was the Egyptian custom of marrying the immediate family member.

After Nefertari, Ramses was known to have loved their daughter Isetnofret. From this union came her successor Bintanath. After Bintanath, the Pharaoh chose another daughter he had by Nefertari, Meritamen. Her sister by the same mother, Nebettawy, took her place. Nearing the end of his life, seeming to have run out of daughters to desire after, he chose Maathorneferure who, scholars suspect, had been either another daughter or his sister.

It is called incest, and the Israelite law which the king and his people were to equally obey severely prohibited such a practice. Leviticus 20:17 called it "a disgrace" if a man marries a sister, "the daughter of either his father or his mother." The law prescribed banishment to anyone guilty of this "disgrace," as the commission of the act discriminated the offender from his God-authored culture. If there was a law that Solomon was not as desperate to violate as gaining for himself a thousand wives, it was experimenting with incest.

But Solomon went for the foreign gals, specifically from the very nations God warned the Israelites never to intermarry with (1 Kings 11:2). And in this matter, he not only modeled after the king of Egypt but even perfected this aspect of his foreign hero.

Though God never sanctioned its arrangement, polygamy and polygyny were acts that had been with man from the dateless past. Solomon's tremendous numerical buildup of wives can be understood from the diplomatic relationship he established and maintained with the nations around him. One can deduce that the peace that marked his reign, described in 1 Kings 4:23–25, may have resulted from accepting wives customarily offered by the kings who negotiated for peace. The arrangement of marriage, therefore, was a significant motion to bind an alliance between parties involved, a mutual sincere reciprocation of goodwill.

The Bible's First Bigamist and his Role in Advancing the Cainite Culture

That was for peace. But the role of marriage serves more than peace. In Genesis 4:19 a man by the name of Lamech expanded the influence of the house of Cain, Adam's cursed firstborn and the Bible's first murderer, by rapidly populating the vast stretches of wild lands untamed by the people of his time. How he facilitated this was through the expedience of a bigamous marriage.

Lamech was the first known bigamist in the Bible. It was his expression of the loose sexual element that marked the Cainite culture that lured the young restless men of Adam's house, the "sons of God" of Genesis 6:2. It was also the best way to promote a counter culture. In the time of Adam, it was his house that dominated the planet. The culture which he promoted and which the world almost automatically embraced was the Godly lifestyle authored by God Himself. Except by Cain, however.

The blessings that came with a righteous life refused to apply to Cain after he murdered his brother Abel. In Genesis 4:11 to 12, his ability to tame crops was nullified by a curse that God slapped on his life. In spite of this, God continued to be gracious by allowing him to live, though wandering the face of the earth (Genesis 4:12 and 14). It did not mean that Cain gained immortal life, impervious to hunger, thirst, exhaustion or pain. He still had to contend with these but without his talent to farm the earth. He needed a new way of living, and in the ensuing verses, it becomes apparent that he did find a way, a compromise that worked around the loss of his talent. In the sixteenth verse, he lived in the land of Nod, east of Eden. The birth of his firstborn Enoch is the first evidence that the new lifestyle he adopted was working. In the seventeenth verse, he gains a following, a considerable one as he establishes the first known city in the Bible. At this point, his pattern of survival was getting noticed and gaining the respect and renown as a workable alternative to the Adamic culture, though at this point it was not seen as an alternative but as an enhancer of certain aspects of life. Four generations later, the Cainite culture explodes from being a minor global player to end the Adamic age and the Godliness it upheld.

The greatest exponent of the Cainite culture, next to Cain, was Lamech. The passage in Genesis 4:19 says that he was married to two women: Adah and Zillah. This multiple marriage was not only responsible for enlarging the increments of population, but out of it came the three fathers of invention that changed the way people lived forever.

"Adah gave birth to Jabal; he was the father of those who live in tents and raise livestock. His brother’s name was Jubal; he was the father of all who play stringed instruments and pipes. Zillah also had a son, Tubal-Cain, who forged all kinds of tools out of bronze and iron" (Genesis 4:20-22).

In Psalm 127:3, it says, "Children are a heritage from the Lord, offspring a reward from him." In the next verse it explains one benefit: "Like arrows in the hands of a warrior are children born in one’s youth. Blessed is the man whose quiver is full of them. They will not be put to shame when they contend with their opponents in court" (verse 4 to 5).

Without the Lord, however, to bless with a quiver full children to contend with their opponents, it seemed like Cain's house was bound nowhere but oblivion. Cain himself took only one wife. It was Lamech who conceived of the daring experiment and accomplished by the flesh what the hand of God could grant.

The psalmist disclosed one benefit of having a large number of offspring in your family. In ancient times, a large family meant power. Children did not survive the starvation that followed a poor man's austere condition; those, however, of a lavishly wealthy family not only did but had more to give and help their neighbor. A wealth of strong male children was a family's insurance that secured its wealth in good hands.

The penchant for the lovely ladies passed on from David to his son Solomon whose fame was built, among others, on the plain fact that he loved “seven hundred wives of royal birth and three hundred concubines” (1 Kings 11:3), maintaining an unbroken violation of God’s condition in Deuteronomy 17:17. Yet if there were any value to virtue in this aspect of his life, it was the fulfillment of the second part of the passage: “…or his heart will be led astray” (Ibid.). And true enough, “his wives led him astray” (1 Kings 11:3).

|

| Andy Sotiriou/moodboard/Corbis |

After Nefertari, Ramses was known to have loved their daughter Isetnofret. From this union came her successor Bintanath. After Bintanath, the Pharaoh chose another daughter he had by Nefertari, Meritamen. Her sister by the same mother, Nebettawy, took her place. Nearing the end of his life, seeming to have run out of daughters to desire after, he chose Maathorneferure who, scholars suspect, had been either another daughter or his sister.

|

| Roger Wood/Corbis |

|

| Alfredo Dagli Orti/The Art Archive/Corbis |

Unlike his father David and King Saul before him, Solomon was not known for his prowess in the battlefield. But it was during his time when the kingdom of Israel experienced great peace "on all sides" (1 Kings 4:24). Countries as far as the Euphrates River to the borders of Egypt brought tribute to Solomon and were his subjects all his life.

|

| Lebrecht Music & Arts/Corbis |

|

| The Gallery Collection/Corbis |

Even as late as the Colonial history, the marriage of King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella of Castile in A.D. 1469 united their two of their Spanish kingdoms and established their government as a world power.

The Bible's First Bigamist and his Role in Advancing the Cainite Culture

That was for peace. But the role of marriage serves more than peace. In Genesis 4:19 a man by the name of Lamech expanded the influence of the house of Cain, Adam's cursed firstborn and the Bible's first murderer, by rapidly populating the vast stretches of wild lands untamed by the people of his time. How he facilitated this was through the expedience of a bigamous marriage.

Lamech was the first known bigamist in the Bible. It was his expression of the loose sexual element that marked the Cainite culture that lured the young restless men of Adam's house, the "sons of God" of Genesis 6:2. It was also the best way to promote a counter culture. In the time of Adam, it was his house that dominated the planet. The culture which he promoted and which the world almost automatically embraced was the Godly lifestyle authored by God Himself. Except by Cain, however.

|

| Zhou Hua/Xinhua Press/Corbis |

|

| Historical Pictures Archive/CORBIS |

"Adah gave birth to Jabal; he was the father of those who live in tents and raise livestock. His brother’s name was Jubal; he was the father of all who play stringed instruments and pipes. Zillah also had a son, Tubal-Cain, who forged all kinds of tools out of bronze and iron" (Genesis 4:20-22).

|

| Araldo de Luca/Corbis |

Without the Lord, however, to bless with a quiver full children to contend with their opponents, it seemed like Cain's house was bound nowhere but oblivion. Cain himself took only one wife. It was Lamech who conceived of the daring experiment and accomplished by the flesh what the hand of God could grant.

|

| National Geographic Society/Corbis |

|

| Fine Art Photographic Library/CORBIS |

Rehoboam, the First Non-Israelite King?

If David's polygamous marriage wrought shocking scandals and disasters in his life, Solomon’s wives and concubines produced an array of interesting contenders to the throne after him, including a half-Israelite, half-Ammonite forty-one-year-old by the name of Rehoboam. It was through Rehoboam that the Israelite kingdom, which kings Saul, David, and Solomon, took painstaking care in establishing all their lives, split into two with the Northern part made up of ten tribes unilaterally slipping into apostasy, and the Southern part preserved for the descendants of David to rule.

If David's polygamous marriage wrought shocking scandals and disasters in his life, Solomon’s wives and concubines produced an array of interesting contenders to the throne after him, including a half-Israelite, half-Ammonite forty-one-year-old by the name of Rehoboam. It was through Rehoboam that the Israelite kingdom, which kings Saul, David, and Solomon, took painstaking care in establishing all their lives, split into two with the Northern part made up of ten tribes unilaterally slipping into apostasy, and the Southern part preserved for the descendants of David to rule.

Rehoboam too took for himself wives and concubines. But unlike the complicated marriages of his immediate two predecessors, the Bible attributes no problems stemming from his eighteen wives and sixty concubines (2 Chronicles 11:21). He did not love them equally, though, for there was one whom he treated with greater favor: Absalom’s daughter Maacah, who must have been specially beautiful if she took after her father who in his time was the most flawlessly handsome man in all Israel (2 Samuel 14:25). From his union with Maacah came Abijah, a favorite he personally groomed above all his other twenty-eight sons (2 Chronicles 11:21). Out of all the disasters that occurred during his reign, Abijah proved to be Rehoboam’s greatest success.

|

| Mimmo Jodice/Corbis |

There may be, however, some discrepancy concerning the Abijah of 2 Chronicles 11:20 and 22 from the Abijah of 13:2. Although extra-Biblical references make no difference between the two, a reader trekking the abovementioned passages may readily differentiate the first Abijah being the son of “Maacah daughter of Absalom” (verse 20) from the second Maacah of 13:2, “a daughter of Uriel of Gibeah.” The dilemma here would therefore concern Abijah’s mother Maacah. Other reliable translations render the word “daughter” of 13:2 as “granddaughter” instead. The man Uriel of Gibeah may have been Maacah’s maternal grandfather. But without looking any further than 1 Kings 15:2, Maacah was identified as the “daughter of Abishalom,” "Abishalom" a variant of “Absalom,” meaning “father of peace.” Later in the tenth verse, Maacah daughter of Abishalom became grandmother to Abijah’s successor, Asa.

But while Asa turned out to be a righteous man of God, Maacah found her niche later in life as a pagan “queen mother” (verse 13) for the goddess Ashera. In accordance to the cultural reform instituted by Asa, the king “deposed his grandmother Maacah from her position as queen mother” (2 Chronicles 15:16).

|

| The Stapleton Collection/Corbis |

Rehoboam first placed Abijah in a prominent position as “chief prince” (2 Chronicles 11:22). It was not a bad decision, in fact, verse 23 says that “he acted wisely.” He spread out his sons to settle various districts of Judah and Benjamin and provided for them lavishly. Among the commodities he provided were wives: “He gave them abundant provisions and took many wives for them.”

The love Rehoboam devoted to Maacah radiated to Abijah who honored that love with a towering respect for his father. In 2 Chronicles 13:7, he defended his father’s honor when he faced Rehoboam’s archenemy, Jeroboam king of Israel:

“Some worthless scoundrels gathered around him and opposed Rehoboam son of Solomon when he was young and indecisive and not strong enough to resist him.”

|

| Patrick Escudero/Hemis/Corbis |

Abijah turned out to be a God-fearing king with an impregnable faith that held God as his leader (verse 12). He came up to Jeroboam with an army of 400,000 against the latter’s 800,000, which got subdued “because (Abijah) relied on the Lord, the God of their fathers” (verse 18). In the verses that followed it is said that Abijah wrested some important towns and villages from Jeroboam’s control and that Jeroboam, after this event, never regained power again during the time of Abijah (verse 19 to 20). The king of Judah, however, “grew in strength” and acquired for himself fourteen wives and by them had twenty-two sons and sixteen daughters (verse 21). In our explanation of “many wives,” we can have some liberty in saying that Abijah’s—and Rehoboam’s—polygamy was within the limits of his ability to control. From the family line touched by Maacah, daughter of Absalom, son of David, Abijah chose Asa, whose great reforms in Judah brought peace throughout the kingdom for three decades (2 Chronicles 11:5 to 6).

[Told you there was more. And there's more!]

[And a lot more there's been! Just finished updating the article with more inserts. Enjoy!]

[And a lot more there's been! Just finished updating the article with more inserts. Enjoy!]

No comments:

Post a Comment