|

| PoodlesRock/Corbis |

"He who is the glory of Israel does not lie or change his mind; for he is not a man, that he should change his mind” (1 Samuel 15:29).

|

| Roberto Herrett/LOOP IMAGES/Loop Images/Corbi |

One important detail that Saul might have forgotten was that the Lord would still maintain to call the Israelites His people. He had no plans abdicating His being Lord and leave His precious possession in the hands of flesh and blood, these hands of flesh and blood, as prophesied by the Prophet Samuel, would subdue His people instead of serve them (1 Samuel 8:11-18). Israel would still belong to God; He would still be the Lord whose approval would install the people’s king. The king would serve as the human political intermediary to consolidate all the tribes of Israel. Through Saul, this was accomplished in 1 Samuel 11:7 to 9 where “the terror of the Lord fell on the people, and they turned out as one man” (verse 7), three hundred thousand men from Israel and thirty thousand from Judah (verse 8).

|

| Lebrecht Music & Arts/Corbis |

|

| Araldo de Luca/CORBIS |

“He will not let your foot slip—he who watches over you will not slumber, indeed, he who watches over Israel will neither slumber nor sleep. The Lord watches over you—the Lord is your shade at your right hand; the sun will not harm you by day, nor the moon by night. The Lord will keep you from all harm—he will watch over your life; the Lord will watch over your coming and going both now and forevermore” (verses 3-8).

|

| Fine Art Photographic Library/CORBIS |

|

| Araldo de Luca/CORBIS |

The promise and the constant reminder to fulfill bringing the Israelites to a land flowing with milk and honey, to make them great, had the absence of a catch. He took a people He called His, brought them “out into a spacious place” and rescued them simply—very simply—because He "delighted in [them]” (Psalm 18:19). All God wanted in return was that His people seek Him (Psalm 14:2; 53:2; 69:32). This is where the betrayal begins, for in the lavishness of God’s grace and the fulfillment of His end of the bargain, His people channeled the devotion that they pledged to offer Him and gave it to the “various gods of the peoples around them…and served Baal and the Ashtoreths” (Judges 2:12,13).

|

| The Mariners' Museum/CORBIS |

God created man in His own image, in His own likeness, by His Holy Spirit. Though it was through His Spirit that He accomplished all creation (Genesis 1:2), it was only into man whom He breathed in His Spirit (2:7). It was a creative process unique from the rest of creation, for which other than Adam did God form from the dust of the ground and breathe into its nostrils the breath of life? In the spiritual realm, such was the process used by God to transform Saul for the kingship:

|

| PoodlesRock/Corbis |

The change in Saul was inconspicuous at first. His uncle noticed nothing special about him after the Spirit came upon him as foretold by the Prophet, though the relative would have strained to study some suspected change in Saul if the latter told him what the Prophet had said about the kingship (1 Samuel 10:16). In the twenty-seventh verse, there were those “troublemakers” who “despised” Saul and “gave him no gifts” while all Israel hailed him their new king. Nevertheless, the transformation of Saul began from the very time he “turned to leave Samuel” (verse 9), even before the Spirit of God descended upon him in power in the presence of the prophets (verses 5 and 10) to perfect the change.

But as we have seen further in the story of Saul, not even the Spirit of God could keep this many away from the will to regress into spiritual corruption. The erosion of Saul’s devotion to God instantaneously took his and his posterity’s anointing away as king.

|

| Ted Spiegel/CORBIS |

Saul’s disobedience on Gilgal foreshadowed his greater backsliding years later when he would be sent to deal with the Amalekites (1 Samuel 15). Gilgal proved to be a costly forewarning that revealed to Saul a vulnerability of his spiritual life he was predisposed to succumbing to; and it was his responsibility to discipline himself in the obedience to the One who had anointed him into kingship. Just like Jesus who had to subdue the weakness of the human flesh, Saul had to deal with the fear that twisted his senses. And with the power of the Spirit of God who right after his baptism told him to do whatever his hand found to do, Saul was more than equipped to execute God’s righteousness on earth, and in his life, for God was with him (1 Samuel 10:7). Similarly, Matthew 4:1 says that Jesus plunged into the wilderness in the power of the Holy Spirit and in this power humiliated His humiliator.

|

| National Geographic Society/Corbis |

But at the end of the challenge, Luke 4:13 explains that the devil left Jesus “until an opportune time.” Jesus’ righteousness may have blown Satan out of the water that time, but the humiliator had plans of returning. It was the same with Saul. It was not enough for the devil that Saul’s dynasty would begin and end in his reign. It was not enough for the devil to rob the posterity of Israel’s first king of the opportunity to be “established…over Israel for all time” (1 Samuel 13:13). If the future held the end for Israel’s first king, then the humiliator would make sure this mighty man of God would live out the rest of his days suffering the humiliating consequence of his disobedience.

|

| Francis G. Mayer/Corbis |

It is flatly a misnomer that this aged evil should be called the humiliator in that he himself had faced great frustration in his main objective to dishonor God. He failed in his goal to take over the throne of heaven with the Lake of Fire waiting for him in the end for him to spend the rest of his eternal judgment (Revelation 20:10).

But it was not enough for the humiliator to allow the fallen king to live out the rest of his days. In John 10:10 Jesus laid out the calling Satan took on to accomplish the humiliation of God and His believers: “steal, kill, and destroy.” Satan had robbed Saul of any chance for any of his descendants to assume power over the throne; he had stolen the right to be heard, answered, and be assisted by God (1 Samuel 28:6). He had succeeded in destroying Saul’s reputation as the firstborn of all the Israelite kings. In the midst of all the elders of Israel’s tribes, his right to be king was torn from him the very day he disobeyed God’s mandate (15:28). Satan destroyed Saul’s sanity and wiped out all logical, emotional, and moral sense to live a normal life, let alone perform his duties as king.

|

| Stapleton Collection/Corbis |

The fear he had succumbed to early in his career upon witnessing the great Philistine army at Micmash had never left him. When his men panicked at the sight of the Philistines in Micmash, so did he (13:11 to 12); when his men felt dismayed and terrified at Goliath’s constant taunting, so did Saul melt away in his tent for forty days (17:11,16). And when he caught the sight of the Philistine army gathered at Shunem, 28:5 says that “he was afraid; terror filled his heart.” Fear, however, was not the only devise the devil used to break Saul. In 1 Samuel 18:8, we find another controlling emotion that was born out of Saul’s greed, ambition, and paranoia: “Saul was very angry.”

|

| The Gallery Collection/Corbis |

It was no doubt Satan had a sadistically swell time detonating Saul’s unstable mood swings between the heights of horror and fury. But nothing would give the devil his most crucial thrill than killing the Lord’s anointed. And in planning Saul’s death, he made sure the basic element of humiliation would be executed in the sight of all his subjects in methodical cruelty.

Pinned on the wall. What Saul tried to do to David and his very son Jonathan finally happened to him.

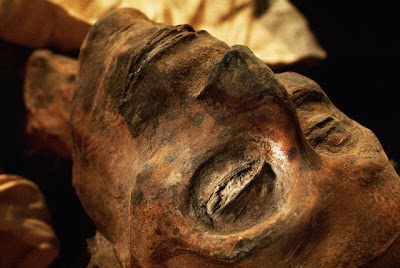

The death of Saul did not come by a simple shot of an arrow or gash of a sword or goring of a spear. It was not as how King Ahab and his son Joram had died by a single arrow cleanly fired between the sections of their armor (1 Kings 22:34, 35; 2 Kings 9:24). The thirty-first chapter of 1 Samuel recounts that he called for death by commanding his armor bearer to strike him down for fear of Philistines humiliation (verse 4). In horror the armor bearer refused and instead stood by and watched Saul take matters into his own hands by driving the sword into himself. For a while Saul lay on the ground as if dead, probably unconscious, which to the armor-bearer was suicide consummated, so he does the same (verse 5). But the armor-bearer assumed wrong. Something happened between the fifth and the sixth verse, which was told in 2 Samuel 1:6 to 10. An Amalekite young man, who happened to be on the site where Saul lay, reported that the king survived his miserable attempt to take his own life.

|

| Werner Forman/CORBIS |

Death did not come easy for Saul and undoubtedly the devil delighted in the pain that baptized him. Then he leads an Amalekite into the king’s convenient service to finish where his attempt had failed. In the tenth verse, the Amalekite confessed:

“’So I stood over him and killed him, because I knew that after he had fallen he could not survive.’”

At a time when the feared Philistines were about to overrun the Israelite camp, the Amalekite had the luxury to be rational and take time to make a precise “objective” notes about the king’s mortal wounds: “…because I knew that after he had fallen he could not survive.” Wow. Observe, on the other hand, how the armor-bearer reacted to the king’s charge: “…the armor-bearer was terrified” (verse 4). It was an aversion that more or less overtook Saul’s soldiers in I Samuel 22:17 when they were told to execute the priests of Nob. The Amalekite, however, held no fear or respect for anything Israelite in the same was as the Edomite Doeg would hold any reverence for the priests of Nob as he singlehandedly put the entire town to the sword (22:18 to 19). The very race God ordered Saul to obliterate had instead gained the upper hand to slay their slayer.

|

| Alfredo Dagli Orti/The Art Archive/Corbis |

|

| National Geographic Society/Corbis |

|

| Sergio Gaudenti/Kipa/Corbis |

Though in intermittent times the soldiers displayed defiance to his orders, the nation of Israel never rebelled against Saul, unlike what happened in the reign of Rehoboam when ten out of the twelve tribes of Israel seceded to form the Northern Kingdom of Israel. It seems that his relationship with God began as a personal matter that later manifested on how things went in the kingdom.

But the people’s clamor for a king, the very matter that sparked the rise of Saul, was in itself a disobedience, and a major one at that since it was even foretold a few hundred years before they settled in the Promised Land. Deuteronomy 17:14 to 20 was a prophecy that carried the convention to be observed when the time Israel should ask for a king. The Prophet Samuel was stung when the people confronted him with this demand. In 1 Samuel 8:10 to 18, Samuel attempted to dissuade the people from asking for a king but God was there to put in His judgment on the matter:

|

| Brooklyn Museum/Corbis |

|

| National Geographic Society/Corbis |

|

| Christie's Images/CORBIS |

|

| Bettmann/CORBIS |

Throughout the desert wandering of the Israelite nation, it was a daily routine for the people to gather this substance at a measure that would be enough for a day’s consumption (verse 4). The thirty-first verse described it as “white like coriander seed and tasted like wafers made with honey,” appearing like “thin flakes of frost” (verse 14) introduced by a layer of dew on the ground. The people called it “manna,” which meant, “What is it?” If God were to answer that He could have said, “It’s my answer to all the ‘pots of meat and…all the food [you] wanted’ in Egypt!” For the “meat” part, He sent flocks and flocks of quail descending into the Israelite camp in the evening (verse 13). So: the people had bread for the entire day and quail for dinner.

And for national security, there was “the angel of God” (Exodus 14:19), the same One who appeared to Moses in the burning bush (Exodus 3:2) believed to be the pre-incarnate Christ Jesus Himself, leading the way, “traveling in front of Israel’s army” (Ibid.), as God intended:

|

| Bettmann/CORBIS |

During the encounter at the Red Sea, however, this angel changed tactical position and went behind the people, followed by the pillar of cloud, “coming between the armies of Egypt and Israel” so that “the cloud brought darkness to the one side and light to the other side” throughout the night “so neither [army] went near the other all night long” (Exodus 14:20). This King fought for His people but yet His people chose against Him for one like them who will “lead us and to go out before us and fight our battles” (1 Samuel 8:20).

|

| Nathan Benn/CORBIS |

|

| David Barnet/Illustration Works/Corbis |

|

| Sunset Boulevard/Corbis |

For those who have seen The Ten Commandments, the line, “Let my people go,” will never be forgotten. Bear in thine mind, however, that Moses never claimed initiative for the statement. Every time he stood before the Pharaoh, he preceded the demand with “Thus saith the Lord” (Exodus 5:1 King James Version).

And if there was someone who was excited about the set up, it was God; not the people. And as we read Genesis 17:8 where God for the first time proposed the set up to the Hebrew father Abraham, we discover the reason for the excitement—note the part I have emphasized:

“The whole land of Canaan, where you are now an alien, I will give as an everlasting possession to you and your descendants after you; and I will be their God.”

|

| Stapleton Collection/Corbis |

And then in Exodus 29:45, God once again, under no provocation, expressed the anticipation: “Then I will dwell among the Israelites”—because what kind of leader lives not among his people?—“and be their God.” It was what God got out of the proverbial deal: to be their God. If the Bible began with the Book of Exodus, we would begin the story of a lonely God atop a lonely peak, unworshiped, unappreciated, unknown, longing to make it big in the lower world of man as a magnet of their love and affection. Yet when begin reading from Genesis, God has held this dream before Him like a luxury from the time before He created the universe, the driving force why He decided to compose a masterpiece out of His own image. The problem, however, started when His masterpiece decided to spill corruption over all what was perfectly created, including on himself. And it has been this corruption that has humiliated God in His desire to be with His people and be their God. For the reason of corruption, God’s Spirit will “not always strive with man” (Genesis 6:3 King James Version) and thus cutting his days short upon the earth up to “an hundred and twenty years” (Ibid.). And because all had become corrupt, all touched by its curse dies, because it is a universal consequence that corruption will always churn out death. This is therefore why the ones God love rebelled as they were ruled by their soul corrupted by the fall of man:

|

| Images.com/Corbis |

“Those who live according to the sinful (corrupted, carnal) nature have their minds set on what that nature desires; but those who live in accordance with the Spirit have their minds set on what the Spirit (of God) desires. The mind of sinful man is death…the sinful mind is hostile to God. It does not submit to God’s law, nor can it do so. Those controlled by the sinful nature cannot please God” (Romans 8:5-8).

When all Israel came up as one man to ask for its king, the Lord called it a rebellion, a rebellion though He was prepared to face. Israel’s refusal to be dissuaded by the Prophet Samuel was an unwitting attempt to humiliate the God who did everything to deliver, provide, protect, and call an over-sized herd of slaves His people, just for them to call Him their God. But God will not be humiliated.

To the nation who asked for a king, He gave them the king they desired: “an impressive young man without equal among the Israelites—a head taller than any of the others” (1 Samuel 9:2), just the type all the other pagan nations around them would have their monarch. A fierce and ruthless champion who would “inflict punishment” (14:47), fight valiantly, defeat, and deliver the nation “from the hands of those who had plundered them” (verse 48)—again, the ideal champion the pagan world would uphold. His heart, however, was just as corrupt as those who hailed him king. No matter how vigorously God attempted to change his heart with His powerful Spirit (10:9), the hostility of his carnal nature would eventually seek to make war against the God who chose him. It was just a matter of time until the disobedience of Saul would surge to overcome his will. And when that day came, God, “before the elders of [His] people and before Israel” (15:30), rejected Saul as king:

| Peter Dawson/Iconica/Gettyimages |

Saul’s disobedience was a slap on the face of God. But God is the real King. As the Prophet Samuel testified, “He who is the Glory of Israel…is not a man” (verse 29). And He who is the Glory of Israel would not take it His face getting slapped by mere flesh and blood. Before the Israel that celebrated his ascent to the throne, God had these rebukes for the king:

|

| Images.com/Corbis |

|

| The Bridgeman Art Library/Gettyimages |

“Does the Lord delight in burnt offerings and sacrifices as much as in obeying the voices of the Lord? To obey is better than sacrifice, and to heed is better than the fat of rams. For rebellion is like the sin of divination, and arrogance like the evil of idolatry. Because you have rejected the word of the Lord, he has rejected you as king” (verses 22-23).

“You have rejected the word of the Lord, and the Lord has rejected you as king over Israel” (verse 26).

“The Lord has torn the kingdom of Israel from you today and has given it to one of your neighbors—to one better than you. He who is the Glory of Israel does not lie or change his mind; for he is not a man, that he should change his mind” (verse 28-29).

Many of us know what it is like to get grilled in front of others; many of us know the experience of being drilled helpless in the sight of those who look up to us as their hero. Before all Israel, God presented them the king they wanted, the king who would make them “like all the other nations” (8:20), complete with the prescribed good looks and the power to survive the bloodbath of the battlefield. God showed Israel what it was like to trust in flesh and blood, in the carnal ideals held by the nations that worshiped lifeless gods of earth and wood, than a God who can split a sea into dry land, rain manna down from heaven in the morning and quail in the evening, and bring victory in a battle no matter how big the size of the enemy army. The humiliation that was meant to be God’s turned into the humiliation of Saul which also was meant to humiliate Israel’s rebellion.

The humiliation of Saul did not stop there. He tenaciously held on to the throne and continued to command the honor of king when he should have returned the authority to Samuel who would have later passed it to David. Because of this, the outcome of his corruption unraveled before all Israel, the Philistine soldiers, and that Amalekite servant that hacked him to death in the battlefield.

God gave Israel a king (verse 22), a king who was as defiant as the people who demanded for him. As the people disobeyed, so did their king.

|

| Bettmann/CORBIS |

God gave Israel a king (verse 22), a king who was as defiant as the people who demanded for him. As the people disobeyed, so did their king.

|

| Ed Darack/Science Faction/Corbis |

The very name of the land the Israelites inherited from God meant "humiliation." The youngest son of Noah's youngest son, Ham, the curse of humiliation fell on Canaan to become "the lowest of slaves...to his brothers" (Genesis 9:25) when Ham one day jeered on his father's drunken nakedness instead of doing the appropriate custom of covering it. Noah, upon knowing later of what Ham did, slapped a curse on his rebellious son by cursing Canaan with humiliation.