|

| ©Image Asset Management/SuperStock |

In 1 Samuel 2:30 to 36, a prophecy was pronounced against Eli’s family ending the role of his “house” and his “father’s house” to “minister before me forever” (verse 30). Entailing this was a bitter judgment upon Eli’s descendants that will “cut short your strength and the strength of your father’s house, so that there will not be an old man in your family line” (verse 31), this because his sons Hophni and Phinehas did not honor Him but treated their calling with disdain (verse 30). According to the seventeenth verse, their sin was “very great in the LORD’s sight, for they were treating the LORD’s offering with contempt.” In the Fourth Chapter, they carried the Ark of the Covenant to battle against the Philistines; the Philistines prevailed, took the Ark, and killed the brothers (verse 11). The curse upon Eli’s House had exerted its reign. But wait, there’s more. A Benjamite messenger sprinted from the battlefield to Shiloh and came straight to Eli and announced the defeat. More concerned with the Ark of the Covenant, the shock pushed Eli off his chair, crushed the vertebra in his neck because of his cumbersome weight, and died (verse 18).

|

| ©SuperStock/SuperStock |

|

| ©SuperStock/SuperStock |

|

| Photo source: www.gorepent.com |

|

| ©Heritage Images/Corbis |

—and by the great Moses in Deuteronomy 33:5—

“He was king over Jeshurun when the leaders of the people assembled, along with the tribes of Israel.”

If they had been called Jews way back then, then God was the King of the Jews. God’s Theocracy was a very simple condition to which the Israelites agreed to: “I will take you as my own people, and I will be your God” (Exodus 6:7). And in this context, God claimed the Israelites for His own, frequently referring to them as “my people.”

The clamor of the people for their own king to rule over them foreboded the end of the time of the Judges. This vehement demand which refused to capitulate even to the words of the Prophet the people loved was the biggest decision of God’s chosen to distance themselves from Him, to considerably limit His hand upon them, to dethrone Him as King—

|

| ©Francis G. Mayer/CORBIS |

This day did not take God by surprise, no siree, for this was an eventuality He had anticipated and even prepared for way back in the wandering Days of their ancestors. In Deuteronomy 17 beginning in the fourteenth verse, God had set up the regulations and parameters of choosing a king to lead them. And in the process, He did not exclude Himself from the examination of candidates—

“be sure to appoint over you the king the LORD your God chooses” (verse 15).

The Prophet Samuel understood this; the people understood this, that’s why they came to him—God’s representative. In the people’s minds the matter was up to the Prophet; in the Prophet’s faith, the matter was up to God. Sure enough, the day before the candidate for Israel’s ever first royal house came to present himself to the Prophet, God had already revealed to the latter that He would be sending “a man from the land of Benjamin” to be anointed leader over all Israel (9:16). On the next day, catching sight of the chosen leader, God confirmed His words: “This is the man I spoke to you about; he will govern my people” (verse 17).

We all know who this was, it was Saul. Now through first impression alone we all know the tragedy attached to the reputation of this king. Yes, God did genuinely choose him to lead His people, but didn’t He pay attention to His foreknowledge that Saul would one day reject Him, disobey Him, and humiliate Him by frustrating the mandate of totally annihilating the Amalekites from the face of the earth, as God had promised from the time these wasteland bandit people pursued and treated the Israelites like wild animals in the desert (Deuteronomy 25:17–19)? Now, hold on: Everything was an open book to God; He knew every detail that would unfold in the future. It was not a matter of knowing, or not knowing, what the future held. Instead, it was everything about giving to the Israelites what they stubbornly demanded of the Prophet Samuel.

|

| Photo source: http://graceofourlord.files.wordpress.com |

|

| Photo source: Wikimedia.org |

|

| Photo source: www.jesuswalk.com |

There is a little bit more to this verse than we have previously evaluated. Notice the desire of the people to “be like all the other nations, with a king to lead us.” Not only did this generation reared their corrupt tantrum before the LORD; they also expressed their desire to be “like the other nations” as the generations before them had gone on to pursue the same aspiration—to be “like the other nations” by worshipping their gods and adopting alien lifestyle never prescribed by the LORD—and perish violently.

|

| Photo source: Wikimedia.org |

“’You have rejected the word of the LORD, and the LORD has rejected you as king over Israel!’ As Samuel turned to leave, Saul caught hold of the edge of his robe, and tore it. Samuel said to him, ‘The LORD has torn the kingdom of Israel from you today and has given it to one of your neighbors—to one better than you’” (1 Samuel 15:26–29).

And that pretty much summed up the spiritual life of the nation of the Chosen. An entire kingdom swayed by a single head, a single head that determined life or death for its people. That single head God had blessed with the knowledge of His Spirit, just as what occurred in the life of Saul when He changed him in Gibeah before he was inaugurated as king (1 Samuel 10:10). God was not all judgment and indignation when the people of Israel asked for a king; He did not go ahead and provide them a king who mirrored their corrupt spiritual condition just to drive that they had made a big mistake in electing Him out of the political limelight. Even in His decision to grant the people their desire, God still made His way to provide for them a king after Him. In 1 Samuel 10:6, the Prophet Samuel prophesied that the Spirit of the LORD would come upon Saul in power, enabling him to prophesy and he would be “changed into a different person.” In the ninth verse—

|

| ©SuperStock/SuperStock |

In spite of this, however, in full knowledge, Saul went on to defy the LORD’s mandate in the Fifteenth Chapter of 1 Samuel. In the very words of God, He confides His disappointment to the Prophet who anointed him king:

“I am grieve that I have made Saul king, because he has turned away from me and has not carried out my instructions” (verse 11).

Let’s just try to analyze this verse. God did not judge Saul for one single mistake of missing out on a directive. If this were so, it picture God as a sore dictator on a rampaging tantrum over a detail. The verse did not say, “he [Saul] has turned away from me because he has not carried out my instruction.” It states instead that Saul had not carried out God’s instructions “because he has turned away from me.” The corruption of the heart took place first then manifested in disobedience.

|

| ©Alexandra Day/Corbis |

|

| Photo source: www.fineartamerica.com |

|

| ©SuperStock/SuperStock |

In the time of Jesus, the kingship was held by a pretender and a foreigner—Herod the Great, an Idumean. One night, foreign delegates from Persia informed him that the real King of the Jews had been born in the country he ruled. Furious, fearful, but tenaciously holding on to the royalty that never belonged to him, Herod took measures to hunt down this newborn King even if it meant slaughtering all infant boys of Bethlehem and its surrounding vicinity (Matthew 2:16). But like David, Jesus had God’s hand upon Him. The night after the Magi had made their visit, God warned Joseph beforehand to take the infant Messiah and Mary and escape to Egypt where they stayed after the death of Herod the Great.

|

| Photo source: www.tarvu.com |

|

| Photo source: wiki.rageofbahamut.com |

• The Temple Hydra

The religious world of Palestine was also as fake as the land’s political set up. According to Biblical historians, the particular period that covered the life of John the Baptist, Jesus Christ, and the early days of the Christians in Israel was considered as the most corrupt episode of religious Israel. For the first time, the office of high priest, which God prescribed for only one person, was held by several, all of a single family of unscrupulous and formidably terrifying political reputation. But the most despicable aspect of this controversy was that none of these pretenders were in any way, shape, or form descended from the house of Aaron, the brother of Moses.

In Exodus 28:1, God handpicked Aaron and his sons to minister before Him as priests. In the fortieth chapter, He commanded Moses to anoint Aaron first, then his sons, in their sacred garments, for the service. “Their anointing,” God said, “will be to a priesthood that will continue for all generations to come” (verse 15). No other family in the Bible was awarded the office of priesthood aside from Aaron’s. In the twenty-fifth chapter of Numbers, Aaron’s house gets blessed with a covenant of lasting priesthood, through the zealous act of Phinehas that turned the anger of God away from the Israelites. The priesthood recognized by the Mosaic culture, therefore, was the Aaronic priesthood.

It was a mandate straight out of heaven shamelessly disregarded in the last fifty turbulent years before Jesus’ birth, when an aristocrat named Annas was appointed high priest in Jerusalem. The nation, probably tired of reacting against their foreign oppressors, tolerated the appointment further when Annas maneuvers to swap and share the office with his son Caiaphas and another relative to accomplish a unique multi-headed mutation of an originally Divine design. Very often in the gospels, the controversial plurality of “chief priests” is confirmed in many passages, beginning in Matthew 2:4 to John 19:21; then from Acts 4:23 to the twelfth verse of Chapter Twenty-Six.

It was a mandate straight out of heaven shamelessly disregarded in the last fifty turbulent years before Jesus’ birth, when an aristocrat named Annas was appointed high priest in Jerusalem. The nation, probably tired of reacting against their foreign oppressors, tolerated the appointment further when Annas maneuvers to swap and share the office with his son Caiaphas and another relative to accomplish a unique multi-headed mutation of an originally Divine design. Very often in the gospels, the controversial plurality of “chief priests” is confirmed in many passages, beginning in Matthew 2:4 to John 19:21; then from Acts 4:23 to the twelfth verse of Chapter Twenty-Six.What was meant to be a single-headed leadership with the high priesthood on top turned into a religious council patterned like a Greek-style oligarchic supreme court. It was almost the four-headed, four-winged leopard monster in the Prophet Daniel’s vision (Daniel 7:6).

|

| ©Brooklyn Museum/Corbis |

|

| ©Fine Art Images/SuperStock |

The success of story woven by the chief priests proved that their corruption had by then seeped deep into the nation’s cultural fiber. The city that killed the prophets and stoned the ones sent to her (Matthew 23:37) had revealed a heart swollen in apostasy and calloused stone-hard from the touch of God. Jesus, in prophetic sorrow, saw a nation on its way to the ground—the grave—when He mourned:

|

| ©Fine Art Images/SuperStock |

Jesus saw a Jerusalem that had cast its lot with the enemies of God. In Luke 19:41, it says that His love for Jerusalem was such that He burst weeping as He approached the city. While a crowd of admirers rejoiced “in loud voices for all the miracles they had seen” (Luke 19:37), Jesus was distressed when at that instant, a vision of the future unfolded before His eyes, which He sadly described:

“The days will come upon you when your enemies will build an embankment against you and encircle you and hem you in on every side. They will dash you to the ground, you and the children within your walls. They will not leave one stone on another, because you did not recognize the time of God’s coming to you” (verses 43–44).

Jesus loved children. During the years of His earthly ministry, He gave importance to the kids. Who will ever forget the ever-famous line, “Suffer little children to come unto me, and forbid them not: for of such is the kingdom of God” (Mark 10:24, King James Version, of course!)? In Matthew 21:16, it is apparent that one of His favorite verses was Psalms 8:2, which says, “From the lips of children and infants you have ordained praise.” In Mark 7:27, He tries to illustrate the priority of His earthly mission with a family norm: “First, let all the children eat all they want…for it is not right to take the children’s bread and toss it to their dogs.” In this story, He heals a daughter of a Syrophoenician woman. In His parable, He used sons; He healed a lot of sons; and daughters, like Jairius’ little girl whom He raised from the dead. Among His most memorable illustrations involves children. He could just put a plug in the dispute among His disciples by setting a little child before them to drive the truth into them: “unless you change and become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven. Therefore, whoever humbles himself like this child is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 18:3 to 4). His words that follow this passage bear a promise for the children: “And whoever welcomes a little child like this in my name welcomes me” (verse 5). Then there was the indignation to anyone who causes “one of these little ones who believe in me to sin”—“it would be better for him to have a large millstone hung around his neck and be drowned in the depths of the sea” (verses 6 to 7).

Jesus loved children. During the years of His earthly ministry, He gave importance to the kids. Who will ever forget the ever-famous line, “Suffer little children to come unto me, and forbid them not: for of such is the kingdom of God” (Mark 10:24, King James Version, of course!)? In Matthew 21:16, it is apparent that one of His favorite verses was Psalms 8:2, which says, “From the lips of children and infants you have ordained praise.” In Mark 7:27, He tries to illustrate the priority of His earthly mission with a family norm: “First, let all the children eat all they want…for it is not right to take the children’s bread and toss it to their dogs.” In this story, He heals a daughter of a Syrophoenician woman. In His parable, He used sons; He healed a lot of sons; and daughters, like Jairius’ little girl whom He raised from the dead. Among His most memorable illustrations involves children. He could just put a plug in the dispute among His disciples by setting a little child before them to drive the truth into them: “unless you change and become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven. Therefore, whoever humbles himself like this child is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 18:3 to 4). His words that follow this passage bear a promise for the children: “And whoever welcomes a little child like this in my name welcomes me” (verse 5). Then there was the indignation to anyone who causes “one of these little ones who believe in me to sin”—“it would be better for him to have a large millstone hung around his neck and be drowned in the depths of the sea” (verses 6 to 7). |

| ©Brooklyn Museum/Corbis |

“Daughters of Jerusalem, do not weep for me; weep for yourselves and for your children. For the time will come when you will say, ‘Blessed are the barren women, the wombs that never bore and the breasts that never nursed'” (Luke 23:28–29).

|

| © Bridgeman Art Library/Gettyimages |

“When Pilate saw that he was getting nowhere, but that instead an uproar was starting, he took water and washed his hands in front of the crowd. ‘I am innocent of this man’s blood,’ he said. ‘It is your responsibility!’ All the people answered, ‘Let his blood be on us and on our children!’” (Matthew 27:24–25)

“When Pilate saw that he was getting nowhere, but that instead an uproar was starting, he took water and washed his hands in front of the crowd. ‘I am innocent of this man’s blood,’ he said. ‘It is your responsibility!’ All the people answered, ‘Let his blood be on us and on our children!’” (Matthew 27:24–25)Innocent blood has a voice and it cries out to God when unjustly spilled. When Adam’s firstborn Cain murdered Abel, God confronted Cain with these words: “What have you done? Listen! Your brother’s blood cries out to me from the ground” (Genesis 4:10). In 2 Kings 21:16, a king named Manasseh who ruled Judah for fifty-five years (verse 1) “shed so much innocent blood that he filled Jerusalem from end to end—besides the sin that he had caused Judah to commit, so that they did evil in the eyes of the LORD.” God later forgave Manasseh who “sought the favor of the LORD his God and humbled himself greatly before the God of his fathers” (2 Chronicles 33:12), rebuilt Jerusalem’s fortification and restored the Temple the way it was before he defiled it with his foreign gods and occult paraphernalia. In spite of these amends, even being succeeded by a God-fearing grandson in Josiah who rediscovered the Book of the Law and had it re-implemented in the cultural mainstream of the land, God would not “turn away from the heat of his fierce anger, which burned against Judah because of all that Manasseh had done to provoke him to anger” (2 Kings 23:26). More than sixty years after his reign, Judah was ravaged by the Babylonians and raiders from Aram, Moab, and the Ammonite kingdom—

“because of the sins of Manasseh and all he had done, including the shedding of innocent blood. For he had filled Jerusalem with innocent blood, and the LORD was not willing to forgive” (24:3 to 4).

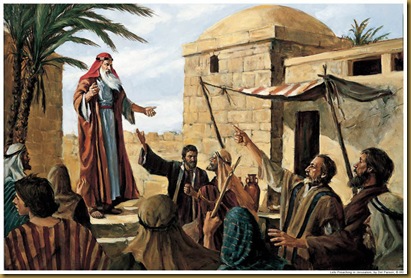

“because of the sins of Manasseh and all he had done, including the shedding of innocent blood. For he had filled Jerusalem with innocent blood, and the LORD was not willing to forgive” (24:3 to 4).As for first-century A.D. Jerusalem, the prophets were proved right. God had uprooted the very nation He established. John the Baptist, years before this, preached about the consequence of hardening their hearts to the voice of God allegory:

“Produce fruit in keeping with repentance. The ax is already at the root of the trees, and every tree that does not produce good fruit will be cut down and thrown into the fire” (Matthew 3:9–10).

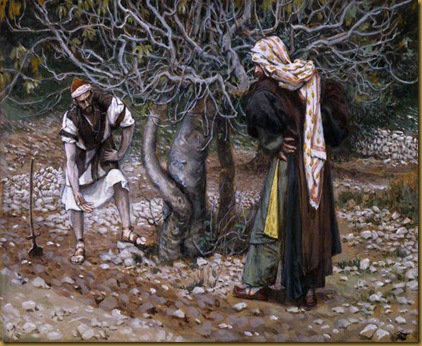

It was perhaps because John had lived closer to the time of Jerusalem’s destruction for the prophecy to have been so vivid in his mind and in the words he spoke. A short time later, John the Baptist was murdered (the story of how he died is told in Matthew 14:1–12 and Mark 6:14–29) by Herod the Tetrarch (Luke 9:9); and a development of the prophecy fell upon the anointing of Jesus. If John’s warning came in the context of producing “fruit in keeping with repentance” (Matthew 3:8), Jesus’ seemed more ominous and inevitable: coming up hungry to a fig tree one day to share of its fruit, He said, “May you never bear fruit again” (Matthew 21:19), when He found nothing of it to eat. “Immediately,” according to the Gospel of Matthew, “the tree withered.” The incident occurred on the morning after He had made His grand entry into Jerusalem and the unexpected incident with the Temple merchants. Jesus was not only a tad closer to the appointed time; He was by then walking the terrain where the Roman siege work would be assembled. Jesus, nonetheless,

delivered the same message that John preached: “And when you stand praying, if you hold anything against anyone, forgive him, so that your Father in heaven may forgive you your sins” (verse 26).

delivered the same message that John preached: “And when you stand praying, if you hold anything against anyone, forgive him, so that your Father in heaven may forgive you your sins” (verse 26).Jesus preached the same message of repentance heard from John. It was one of the comparisons drawn between the cousins that made people, including Herod the Tetrarch, suspect that John had resurrected after his execution (Matthew 14:2; Mark 6:14, 8:28; Luke 9:19). The urgency in His words, however, was apparently more distressful when He alluded to the destruction of Jerusalem. While John saw the “ax…already at the root of the trees,” Jesus in a parable He shared in Luke 13:6 to 9 envisioned a garden owner just itching to use that ax:

“A man had a fig tree, planted in his vineyard, and he went to look for fruit on it, but did not find any. So he said to the man who took care of the vineyard, ‘For three years now I’ve been coming to look for fruit on this fig tree and haven’t found any. Cut it down! Why should it use up the soil?’ ‘Sir,’ the man replied, ‘leave it alone for one more year, and I’ll dig around it and fertilize it. If it bears fruit next year, fine! If not, then cut it down.’”

“A man had a fig tree, planted in his vineyard, and he went to look for fruit on it, but did not find any. So he said to the man who took care of the vineyard, ‘For three years now I’ve been coming to look for fruit on this fig tree and haven’t found any. Cut it down! Why should it use up the soil?’ ‘Sir,’ the man replied, ‘leave it alone for one more year, and I’ll dig around it and fertilize it. If it bears fruit next year, fine! If not, then cut it down.’”The context of this parable was based on a conversation that revolved around the heinous massacre of a number of Galileans whose blood was used by Pontius Pilate to desecrate their sacrifices with. It was current events at the time. What did you think? All Jesus and His disciples ever talked about were super spiritual matters? He may have been God, but He was human too, you know. And in verse 4, His statement about “those eighteen who died when the tower in Siloam fell on them,” proved that He was very much aware and actively evaluating the temporal events of His country! In the same way as we interpret “great earthquakes, famines and pestilences in various places, and fearful events and great signs from heaven” as foretokens of the end of the age (Luke 21:11), Jesus pointed out that the subject of their discussion entailed a spiritual warning that the end of Jerusalem was just a few years away. But unlike the daily news that provides no single alternative to avert or evade an impending tragedy, Jesus taught: “Unless you repent, you too will all perish” (verses 3 and 5).

• The Hellenistic Beasts

Right before the destruction of Jerusalem, the religious hydra of the land that had gained a greater murderous clout, which sparked among the Hellenistic Jews in Jerusalem, had triumphantly chased away the children of God—the believers—out of the city. Until the Hellenistic Jews became involved, the chief priests, who were Hebraic Jews, could only arrest the believers (Acts 5:18)—the Apostles, in particular—detain them in prison for but overnight (Acts 4:3), warn them not to speak about Jesus’ name again (Acts 4:18,21, 5:28), and then send them home singing praises to God (Acts 5:41). The worst the chief priests could do to the believers was have them flogged (verse 40). This was because the leaders who pushed for the death of Jesus “feared that the people would stone them” should they use force upon the Apostles (Acts 6:26). But with the involvement of the Hellenistic Jews, things became more brutal.

Right before the destruction of Jerusalem, the religious hydra of the land that had gained a greater murderous clout, which sparked among the Hellenistic Jews in Jerusalem, had triumphantly chased away the children of God—the believers—out of the city. Until the Hellenistic Jews became involved, the chief priests, who were Hebraic Jews, could only arrest the believers (Acts 5:18)—the Apostles, in particular—detain them in prison for but overnight (Acts 4:3), warn them not to speak about Jesus’ name again (Acts 4:18,21, 5:28), and then send them home singing praises to God (Acts 5:41). The worst the chief priests could do to the believers was have them flogged (verse 40). This was because the leaders who pushed for the death of Jesus “feared that the people would stone them” should they use force upon the Apostles (Acts 6:26). But with the involvement of the Hellenistic Jews, things became more brutal. The Hellenistic Jews were different from the Hebraic Jews. It can be understood to this day that there is an overwhelming urge for a Jew to return to the land God has given him. It has been this way since the Apostles’ time. The Hellenistic, or Grecian, Jews were such who retained their Jewishness but adopted Greek cultural trappings, which, among others, included name, education, language, profession, and clothing. Because they were adapted to foreign life from birth, much of the Mosaic culture was unfamiliar to them.

The Hellenistic Jews were different from the Hebraic Jews. It can be understood to this day that there is an overwhelming urge for a Jew to return to the land God has given him. It has been this way since the Apostles’ time. The Hellenistic, or Grecian, Jews were such who retained their Jewishness but adopted Greek cultural trappings, which, among others, included name, education, language, profession, and clothing. Because they were adapted to foreign life from birth, much of the Mosaic culture was unfamiliar to them.An example of this was the young Timothy of Lystra in Acts 16, whose mother was a Jewess and his father a Greek (verse 1). The third verse relates that the young man had not yet undergone the rite of circumcision until the Apostle Paul came to their home. Wanting to take him along in his missionary journey, the Apostle performed the circumcision on Timothy as a necessary measure to gain the confidence of the Hebraic brethren and establish his credibility among them.

| |

| ©SuperStock/SuperStock |

Because of the weakness the chief priests possessed in prosecuting and stopping the Jesus faith from swallowing the Mosaic society, a particular group of Grecian Jews, who felt they had nothing to lose, were just too desperately reckless to go to the extent of applying murder on the enemies of their Hebraic brethren.

Now, not all Hellenistic Jews gravitated towards the Mosaic religion; there were also those who became Christians. The story in Acts 6 begins with the friction between the Grecian and Hebraic Jewish believers. The Apostles, who were Hebraic, thought of solving the issue by appointing a seven-man committee, known to us today as deacons, to directly address the issue of the Grecian widows neglected in the daily distribution of food (verse 1). The fifth verse introduces the seven, all with Greek names, which means the Church’s first deacons were Hellenistic Jews. The Grecian membership loved the idea (verses 3 to 4). So while the Church had decisively solved the equality problem between the Hellenistic and the Hebraic, the Mosaic society was still getting into gear with its solution.

Now, not all Hellenistic Jews gravitated towards the Mosaic religion; there were also those who became Christians. The story in Acts 6 begins with the friction between the Grecian and Hebraic Jewish believers. The Apostles, who were Hebraic, thought of solving the issue by appointing a seven-man committee, known to us today as deacons, to directly address the issue of the Grecian widows neglected in the daily distribution of food (verse 1). The fifth verse introduces the seven, all with Greek names, which means the Church’s first deacons were Hellenistic Jews. The Grecian membership loved the idea (verses 3 to 4). So while the Church had decisively solved the equality problem between the Hellenistic and the Hebraic, the Mosaic society was still getting into gear with its solution.In the ninth verse, the opportunity presented itself when the Grecian Jew of the Church crossed paths with the Grecian Jew of the Mosaic "Synagogue of the Freedman" (Acts 6:9), which was constituted by the “Jews of Cyrene and Alexandria as well as the provinces of Cilicia and Asia.” This particular synagogue came into opposition to the Christian deacon Stephen while he was doing “great wonders and miraculous signs.” The men of the Freedman Synagogue, wanting to snare the man of God into speaking blasphemy “against Moses and against God” (verse 11), methodically stirred up the people, the elders, and the teachers of the law to seize Stephen and bring him before the chief priests. Notice in the fourteenth verse that the ultimate objective of respect in a predominantly Hebraic society was very manifest from the allegation of this Freedman mob: “For we have heard him say that this Jesus of Nazareth will destroy this place and change the customs Moses handed down to us.”

What happened next was a tremendous Spirit-filled educational discourse that neither the Hebraic nor the Hellenistic in that trial ever thought of getting. And then it happened. At a speech as if being delivered by Jesus Himself—with the words, “Was there ever a prophet your fathers did not persecute? They even killed those who predicted the coming of the Righteous One?” (Check out Matthew 23:37, “O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, you who kill the prophets and stone those sent to you….”)—the Greek-schooled folk, who were supposed to have been taught sophistication and emotional restraint, erupted into a bestial pandemonium, furiously “gnashing their teeth at [Stephen]” (7:54), covering their ears, “yelling at the top of their voices” (verse 57). They all stampeded toward Stephen, “dragged him out of the city” and stoned him until he died (verse 58). At this, Christianity gained its first martyr. If the chief priests hid behind the crowd they manipulated against Jesus, the Freedman mob got down and dirty and drew the blood of Stephen with their own hands.

What happened next was a tremendous Spirit-filled educational discourse that neither the Hebraic nor the Hellenistic in that trial ever thought of getting. And then it happened. At a speech as if being delivered by Jesus Himself—with the words, “Was there ever a prophet your fathers did not persecute? They even killed those who predicted the coming of the Righteous One?” (Check out Matthew 23:37, “O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, you who kill the prophets and stone those sent to you….”)—the Greek-schooled folk, who were supposed to have been taught sophistication and emotional restraint, erupted into a bestial pandemonium, furiously “gnashing their teeth at [Stephen]” (7:54), covering their ears, “yelling at the top of their voices” (verse 57). They all stampeded toward Stephen, “dragged him out of the city” and stoned him until he died (verse 58). At this, Christianity gained its first martyr. If the chief priests hid behind the crowd they manipulated against Jesus, the Freedman mob got down and dirty and drew the blood of Stephen with their own hands. “On that day,” according to Acts 8:1, “a great persecution broke out against the church at Jerusalem”—led by these Grecian-educated social climbers acting no different from the mindless orgiasts under the Bacchanalian moonlight, which they had undoubtedly learned about in the marbled universities of Greece, Rome, and Asia Minor—“and all except the apostles were scattered throughout Judea and Samaria.” The death of Stephen marked a new phase in Christianity in that it got thrown toward the Mediterranean border of Jewish Palestine; it also marked the decline of the church in Jerusalem. In the same chapter in the Book of Acts, we find the Samaritan ministry of Philip (verse 4 to 8), another deacon, and his Ethiopian encounter (verses 26 to 40); Simon Peter also began fortifying the Samaritan frontier in 8:9 to 25. Blown out of the water, so to speak, were the Christians in Jerusalem and very quickly then after did local fellowships begin sprouting at the periphery of the western Jewish borders, such as the ones in Damascus, Antioch, and Cyprus (Acts 11:19). And they flourished there.

“On that day,” according to Acts 8:1, “a great persecution broke out against the church at Jerusalem”—led by these Grecian-educated social climbers acting no different from the mindless orgiasts under the Bacchanalian moonlight, which they had undoubtedly learned about in the marbled universities of Greece, Rome, and Asia Minor—“and all except the apostles were scattered throughout Judea and Samaria.” The death of Stephen marked a new phase in Christianity in that it got thrown toward the Mediterranean border of Jewish Palestine; it also marked the decline of the church in Jerusalem. In the same chapter in the Book of Acts, we find the Samaritan ministry of Philip (verse 4 to 8), another deacon, and his Ethiopian encounter (verses 26 to 40); Simon Peter also began fortifying the Samaritan frontier in 8:9 to 25. Blown out of the water, so to speak, were the Christians in Jerusalem and very quickly then after did local fellowships begin sprouting at the periphery of the western Jewish borders, such as the ones in Damascus, Antioch, and Cyprus (Acts 11:19). And they flourished there. |

| ©The Gallery Collection/Corbis |

|

| ©SuperStock/SuperStock |

|

| ©SuperStock/SuperStock |

|

| ©Fine Art Images/SuperStock |

|

| ©SuperStock/SuperStock |

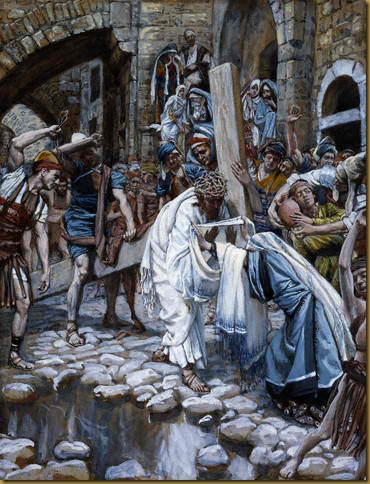

Did the Jews kill Jesus? It's an age-old question that has spawned hatred, erroneous doctrine, dead-wrong Bible interpretations, and deadly religious beliefs. So, did they?...kill Jesus? No. Them Jews did not kill Jesus, period. Not even them Roman sadists killed Him! In fact, when He prayed, "Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing" (Luke 23:34), He was praying for the cold-hearted Roman soldiers who, despite torturing Him and nailing Him on the cross, were just following their orders from their superiors. When Peter drove his point in his Pentecost message and said, "God has made this Jesus, whom you crucified, both Lord and Christ" (Acts 2:36), he was alluding to the rebellious spirit that the people needed to repent of; there was no intention to slap them with guilt and accusation. The Jewish people loved Him! He came to them healing, feeding, and preaching deliverance. How could anyone not love Him? He loved kids! He brought hope. Sure, there were those who got offended in His teaching when they thought He was talking about cannibalism about eating His flesh and drinking His blood, but an entire nation did not hate him. Those He helped and loved loved Him back and followed Him as a crowd mourning Him while He staggered all the way to Calvary with that heavy cross on His back. Lots of Jews may have hated Him; lots of Jews may not have cared about Him; but lots of them also loved Him. And lots of them came to understand and love Him when the apostles took on their ministry, preaching the same message that was distinctly Jesus all over. Who killed Jesus? The chief priests. These were the ones who schemed and planned with all the proverbial itch in their body! And why did they scheme and plan? Because they were scared of the people (Matthew 21:46; Mark 11:18, 12:12; Luke 20:19, 22:2). And why were they scared of the people? Because the people loved Him and one false touch from anyone might cause a riot—something that the Roman authorities might handle with unmitigated cruelty and which will eject them chief priests out of business!

|

| ©Universal Images Group/Superstock |

Now, when we say business here, we just don't mean religious business. We categorically do not mean taking care of the spiritual lives of the people. We mean financial business—ch-ching, ch-ching! b-bling, b-bling! The annual worth of a high priest in those days already stood at 8 million dollars by today's standard. He raked an annual salary of about 16 million dollars and amassed commissions, among which came from the sacrificial animals sold in the Temple area that brought him an average $8 per approved sacrifice. This data alone will explain why Annas, Caiaphas, and the other members of the Temple hydra would send a Jesus to His death and smash the brains out of a kindly Grecian Jewish Christian deacon who did nothing but share food and the Gospel to whom he thought were the underdogs of a Mosaic society. The Jews did not kill Jesus; the masters who controlled them—who just happened to be Jews—did!

And you thought thirty pieces of silver was just about it concerning the Temple Hydra. Well, how about the time when Jesus turned the tables on the moneychanging Temple scam on His first day in Jerusalem?

|

| Photo source: http://achristianpilgrim.wordpress.com |

|

| ©Sandro Vannini/CORBIS |

In the face of possible extinction or stagnation, God gave the believers a man who would sow the seeds of church growth and hew for the believers a doctrine that would liberate them from the clutches of an old tradition.

|

| ©SuperStock/SuperStock |

• Paul

He was a Jew, raised in Tarsus, a city in the vicinity of Cilicia. Despite the Hellenistic setting of his youth, he was strictly reared a Hebraic. At an early age, he was brought to Jerusalem to study at the feet of a great Hebraic teacher named Rabbi Gammaliel to become a Pharisee. By age thirty, some scholars suspect, he was already a member of the Sanhedrin. He was about Jesus' age, according to historians, when came to Jerusalem about the same time Jesus began His ministry; the two never met, though. He is first mentioned in the Bible as Saul of Tarsus (Acts 8:1), as one who stood by and gave approval to the stoning of the Christian deacon Stephen. He declared himself an enemy to those who followed the Way (9:2) and militantly pursued them, "whether men or women...[to] take them prisoners to Jerusalem" (Ibid.). From this point alone, history proved him to be a life-changer in that his infamy struck fear in the hearts of the Christian believers. In Acts 9:13, panic was all over the Godly Ananias at the mention of the name. Note that where there was supposed to be a "Yes, Lord, I will obey," a wealth of words instead issued out of his databanks:

|

| ©Christie's Images/CORBIS |

"'Lord,' Ananias answered, 'I have heard many reports about this man and all the harm he has done to your saints in Jerusalem. And he has come here with authority from the chief priests to arrest all who call on your name.'"

That reminds us about ourselves when God at some time told us to do the right thing and then we went, "God, You gotta be kidding!" But the simplicity of His virtue alone is enough to nag the bad attitudes out of us and get us back on track to Him!

In another passage, in verse 26, even the apostles recoiled in fear at the sight of him. This guy was bad news. If the believers in those days had a Believers' Broadcasting Network, it wouldn't take a lot of air time to send the folks running for cover if the newscaster would merely say, "Saul of Tarsus."

In one of his missions, however, he had a God encounter. Through this, it was the life-changer's turn to get his life changed. Forever.

|

| ©Stefano Bianchetti/Corbis |

|

| ©Alinari Archives/CORBIS |

A combination of knowledge that came from years of studying the Holy Scriptures and the fiery fervor of a man with the Truth made him an unstoppable force that baffled his target audience which he wanted to win for Jesus (verse 22). There was, however, some learning of value here. His knowledge and fervor made him too unstoppable and the immovable advocates of Judaism were not amused one bit. In the twenty-fourth verse, Saul learned of a plot to murder him sending him fleeing for his life out of Damascus and into Jerusalem. In the nation’s capital, he tried to enter the apostles’ church but his infamy just blew him out of the doors. Eager to do his share and win souls for Jesus, however, he marched right for the “Grecian Jews” —these guys!—and tried to debate with them and tried to get himself killed (verses 28 and 29). Immediately, “the brothers” (verse 30) swooped down to his rescue and then sent him off to Tarsus.

|

| ©Image Asset Management Ltd./SuperStock |

|

| ©Historical Picture Archive/CORBIS |

|

| ©Brooklyn Museum/Corbis |

|

| ©Richard T. Nowitz/CORBIS |

Through all of these, one thing we could learn between the Christians and the Jews is that both seem to form the two sides of a coin; and I say coin because each of them had an inability to look at the other while one was undergoing a crisis. It was just too bad because they could have learned much from each other well. History shows us that the Jewish believers underwent the very same problems, dilemmas, and ordeals that the Christians believers did; the flight from Jerusalem was the first. If the Jewish believers took a hint of the plight of the Christians when they were sent scattering all over the Roman Empire, there might have been some measures taken—like the repentance that John the Baptist, Jesus, and the apostles had preached—to minimize or even avert the tremendous slaughter that occurred during 70 A.D. and the reprisals of 113 A.D. and 132 A.D. If the Jewish believers had taken note of the extreme religious persecution the Hellenistic Jews had put the Christians through, they might have considered it a glimpse of their future when the Jewish people too would undergo the same treatment from the nations they sought refuge in during the centuries after 135 A.D., when Jerusalem and Judaean Palestine was made off-limits to the Jews by the Romans, until May 14, 1948, a Friday, at 4 p.m., when the Israeli state was born.

|

| ©Bettmann/CORBIS |

|

| ©SuperStock/SuperStock |

“He answered, ‘I was sent only to the lost sheep of Israel’” (Matthew 15:24).

“These twelve Jesus sent out with the following instructions: ‘Do not go among the Gentiles or enter any town of the Samaritans. Go rather to the lost sheep of Israel. As you go, preach this message: The kingdom of heaven is near’” (Matthew 10:5–7).

Through the message of the Gospel, Jesus was able to save a great remnant for God’s people and for Israel, as God has always done before.

Now we understand that God did meet the expectation of the Jews for deliverance when Jesus came to them as the “Suffering Servant” of Isaiah 53. While we still see the said passage in a largely spiritual context, God did intend to rescue Israel from the “day of the Lord’s vengeance” (Isaiah 61:2), which He later described in detail in Luke 21:22 as the “days of vengeance, that all things which are written may be fulfilled” (King James Version):

|

| Photo source: http://www.preteristarchive.com |

We saw in our previous article that Jesus came to reclaim the High Priesthood and, in His death and resurrection, He accomplished this. But just like the anguish of His people of old, their cries have gone to the point—once again, which also goes for the buildup of sin!—that has reached up to heaven, and He has to, once and for all, raise a Leader to deliver His people and rid them of all the sin that was corrupting them. It was like way back in the days of Sodom and Gomorrah, only this time, He sends no two angels. MORE TO COME.