The book is Eaters of the Dead (Ballantine Books: New York, 1991) by the late great Michael Crichton (October 23, 1942–November 4, 2008), a translation of a text penned around 922 A.D. by an Arab diplomat by the name of Ahman Ibn Fadlan, an official of the Caliph's court who fell from royal favor after meddling with a nobleman's wife. To appease the nobleman, the Caliph sent Ibn Fadlan on an assignment to establish ties with the Bulgars up in the largely unexplored recesses of the frozen north, of which the only person expecting Ibn Fadlan to return from was...Ibn Fadlan.

|

| ©Christel Gerstenberg/CORBIS |

Ibn Fadlan was a diplomat as easily seen in the manner he documented his journal. But while he held on to his dignity as a representative of Baghdad, the City of Peace, there were instances when he could not withhold his outrage over matters of the Northmen manners and customs which he found appalling and reprehensible. But this was not always the case; for the most part, he maintained the tone of a news reporter and held his facts under the strict acumen of a level-headed dispassioned observer who in addition, stayed out of the way.

|

| © Markus Hermenau_Westend61_Corbis |

And there was nothing more he wanted than to stay out of the way. In the book. Ibn Fadlan freely confessed how much he had no stomach for battle. But yet he found himself in battle and much blood splattered around him. What was he doing in the middle of all this? Well, in the first place he shouldn't have gone along with those Vikings.

Here's what happened: For a year, Ibn Fadlan was with a company of Arab officials that led him up to Turkey. When they reached the more rugged part of the country, the group changed as some officials left while Turkish guides took their place. Upon approaching the Volga River, Ibn Fadlan's core group was supposed to be taken up the river by a contingent of Vikings till they reach the Kingdom of the Bulgars, around 600 miles east of what is now modern Moscow. For some reason, the Vikings denied Ibn Fadlan's his group their freedom to continue with the mission, even to the point of knife-point (1). Instead, all of them would continue up the Volga, farther northward, into a land called Venden, ruled by a king named Rothgar who was a close relative of the leader of the Viking company.

RIGHT PICTURE SOURCE: https://s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com

The Viking squad looked up to a tall, young, and very strong chieftain by the name of Buliwyf. Ibn Fadlan described him of having "the bearing of a leader" (2). Having to behold the Northman the first time was overwhelming for the Middle Eastern diplomat. He wrote:

"Never did I see a people so gigantic: they are as tall as palm trees, and florid and ruddy in complexion" (3).

|

| © 2015 Frank Frazetta |

It was therefore an amazing sight for Ibn Fadlan to have witnessed the evidence why the Northmen chose Buliwyf as their leader. And not only was Buliwyf a chieftain; he was about to become king. Ibn Fadlan arrived at a crucial time when the tribe's existing king was dying of a worsening illness of which none believed was there any recovery. In a span of a few days, the king was dead. But instead of Buliwyf immediately taking over the throne, the assurance of the kingship was somewhat derailed by the lack of appropriate guidelines and protocol on leadership succession in the event an incumbent king dies of sickness and not of falling in battle. Furthermore, Buliwyf was not the only candidate for supremacy.

|

| © 2015 Frank Frazetta |

From the mountainous region of Venden, a mesenger sailed to appeal for Buliwyf's help. His uncle, the king named Rothgar, had incurred the curse of an ageless terror that attacked in the night, even under the cover of a black mist. In Viking tongue these were called the "wendol," or "mist monsters." The very idea of these creatures silenced the Northmen, including the great Buliwyf himself. According to their custom, there were two things one did not do in regards to the monsters: utter its name and launch out into the mist wherever it appears. Ibn Fadlan, a highly educated Arab nobility during the height of the Muslim civilization, could not comprehend at first what Nordic superstition was there for them to fear a mist. It took several explanations and later on a first-hand encounter with these beings that made him understand.

|

| A scene from the 1999 Touchtone Pictures' film The 13th Warrior. |

|

| © Christophe Boisvieux/Corbis |

The Vikings and Writing. We know Vikings utilized writing in practical everyday matters like cataloging business items as they were also traders, aside from their popular reputation of terrific warriors and pirates. Historically, Vikings associated some magic to writing. It is no surprise to us today that the Viking runes are associated with magic, clairvoyance, and foretelling the future. They were etched on a weapon for several purposes: to indicate the name of its owner; to endow the device with magical power and give its wielder strength in battle. Vikings also scratched runes on special rocks to remember dead family and friends. This may have been the concern which came over Buliwyf's lieutenant Ecthgow when he saw his name being scratched on the ground by Ibn Fadlan:

"Now Ecthgow, the lieutenant or captain of Buliwyf, and a warrior less merry than the others, a stern man, spoke to me through the interpreter, Herger. Herger said, 'Ecthgow wishes to know if you can draw the sound of his name.' I said I could, and I took up the stick, and began to draw in the dirt. At once Ecthgow leapt up, flung away the stick, and stamped out my writing, He spoke angry words. Herger said to me, 'Ecthgow does not wish you to draw his name at any time, and this you must promise. Here I was perplexed, and I saw that Ecthgow was angry with me in the extreme. So also were the others staring at me with concern and anger. I promised to Herger that I would not draw the name of Ecthgow, or of any of the others. At this they were all relieved'' (4).

"Do you work for my brother?" Remember this scene in the movie Stardust? Decisions were made based on some runic symbols being tossed in the air.

Generally, Vikings did not write much but committed a lot to oral tradition, including poems and stories short and long like Beowulf. This may be because they did not have paper, parchment, or materials of the like, but instead needed to scratch or chisel their runes on wood or stone. On the matter of the spirituality of the written symbols, Vikings regarded their runes as a gift from their chief god Odin, which is why they treated their native symbols with great respect. But while Ibn Fadlan's symbols were not runes, they were nonetheless dedicated to a deity —"Praise be to God" (5)—which was enough for Buliwyf and his gang to revere, explaining the silent amazement they maintained while gazing at the Arabic symbols.

|

| A page of the original Ibn Fadlan manuscript. |

Ibn Fadlan outlined Buliwyf's adventure with the journey to King Rothgar's country as the first part; the battle with the mist monsters as the second; the thirteen's infiltration of the monsters' lair to assassinate the matriarch, the third; and fourth, their clash with the "glowworm," or the full force of a furious wendol army.

The Ibn Fadlan report was accomplished around 926 A.D. after a three-year adventure with Buliwyf and his Northmen warriors. The Arab ambassador never accomplished fulfilled his mission to the Bulgars, as far as Eaters of the Dead is concerned, and whatever happened to his report—how the Caliph received it—is never known, though it went on to become the earliest known eyewitness account of Viking life and society (6).

Through time the manuscript had fallen into the hands of some careful owners that treated it as treasure. Among these was a thirteenth-century Arab named Yakut ibn-Abdallah who used the facts in the report to complete a geographical lexicon he was putting together. This indicates that the manuscript did survive upheavals through time.

|

| © Arne Hodalic/CORBIS |

ABOVE: A 13th century Arab illustration from a manuscript depicting a merchant's sailing dhow. Sultanate of Oman, 1994.

According to Crichton's summary of the manuscript, fragments of it and of other versions, even of those "of dubious origin" (7) have been discovered all over Europe with the earliest dating back to 1047 A.D. One notable composition goes back to the sixteenth century, written in Latin, and contains the material about the Oguz Turks and passages relating the battle with the wendol. It has been claimed that the translation was derived directly from an Arabic text (7). Another text which allegedly contains Ibn Fadlan's relationship with the Caliph was found in a monastery situated northeast of Thessalonica, Greece. The date of writing remains uncertain but was penned in Medieval Latin (7).

Crichton seemed to have lamented on the lack of scholarly concern of past experts to consider what treasure they had in the Ibn Fadlan report which eventually led to its partial disintegration. On the other hand, we should also not readily devalue the documents that came after the original, wielding their inaccuracies. In a way we can understand that these were acclamation for the inspiration delivered by the original as it passed from owner to owner, from one place to another. These are undoubtedly a manifestation of the influence of the Ibn Fadlan manuscript, its account copied into a mold that altered the complexion and merged with a new author's creative opinion of what should have been.

While Yakut ibn-Abdallah looked to the Ibn Fadlan report as a source of information for his geographical lexicon, one Anglo-Saxon manuscript seemed to have taken great interest in the prowess of Buliwyf. This particular piece of writing contained most of the names, places, and events, that appeared in the original, yet rearranged into what later became one of greatest heroic epics ever written.

Beowulf

The Anglo-Saxon manuscript does not make mention of any author from the deserts of the Middle East but experts trace its style from a sophisticated man of letters writing for a courtly audience. It does not speak of a foreign thirteenth warrior or any spiritual group of warriors but a passage mentions the hero sailing to Rothgar's kingdom in a company of fifteen. It does not speak any tribe of monsters that attack in the mist, but affirms one rampaging brute and its mother that had slaughtered Rothgar's bravest. And though the names Rothgar, Hygelac, Wulfgar, Ecgtheow, and the Hurot Hall all appear in this scripture, "Buliwyf" does not.

The name of the hero of this story is Beowulf and he had been summoned by his uncle, King Rothgar, to contain a menace called by many titles in the scriptures—the Fiend of Hell, that grim Hobgoblin, the greedy one, the fierce one, that skulking Shade of Death, this Foe of mankind, Stalker lone by night, the hugest of night horrors—but ultimately goes by the name Grendel. As in the Ibn Fadlan story, this monster was lured by the revelry in the Hurot Hall massacring thirty of Rothgar's mightiest Danes. The great mead hall was shut down after that night, boarded up tight as with all the other houses in the kingdom by nightfall. But this was about to end with the arrival of Beowulf.

|

| SOURCE: students.ou.edu |

Rothgar and his Danes found this a matter to celebrate. For Buliwyf, it was a situation more ominous than before. The wendols they faced were but an experimental force which for the first time was sent back reeling after a bloody clash. The Vikings were sure of a second bigger wendol attack that would shortly come after and of which would surely destroy them all (8). Buliwyf and his men knew that their only recourse to save the kingdom would be a preemptive attack on the lair of the wendol. So notwithstanding fatigue and weakness resulting from the recent skirmish, Buliwyf and his commandos immediately set out on horseback to take the battle to the enemy.

|

| The 13th Warrior ©1999 Touchtone Pictures |

To augment his god-given strength and ensure the death of the monster, Beowulf was handed a magical sword which bore the name Runding. In Ibn Fadlan's account, Runding was known as "the power of the ancients, the power of the giants" (9), a power he was entitled to wield being a chieftain. But it was also represented as a sword and with it he took with him and used it till his final battle with the wendol (10).

LEFT: The scramasax, a Viking sword with runic inscriptions on its blade for god-blest results.

Beowulf soon descends into the den of the monster and successfully slays the menace. Buliwyf likewise, considerably debilitating the enemy force but emerges from the lair mortally wounded from his battle with the mother. He did finish her off in a duel, but not without a price: "A silver pin, such as a pin for hair, was buried in his stomach: the same pin trembled with each heartbeat. Buliwyf plucked it forth, and there was a gush of blood. Yet he did not sink to his knees mortally wounded, but rather he stood and gave the order to leave the cave" (11). By the time the Viking commandos reached the safety of their exit, Buliwyf crumpled to the ground. His lieutenant Ecthgow took charge of him till they made it home to Rothgar's kingdom (12).

The adventure of Buliwyf and his brave Viking fighters took place in a span of a few months. There were three battles with the wendols each spaced a few hours. The imminence of the final battle came "an hour before dawn" (13), when the full force of the wendol army came in a trail of torch fire that looked like a "glowworm dragon" (14), as Herger, Ibn Fadlan's interpreter, described it. In the Beowulf story, it took fifty years after Beowulf had become king of the Geats when the threat of a glowworm descends on his kingdom.

Unlike the glowworm dragon faced by Buliwyf, Beowulf faced a real dragon. The shadow of this dragon emerges after a thief steals a precious jeweled goblet from its treasure cache. The loss enrages the firebreather and takes it out on the hapless homes and properties of Beowulf's kingdom. Beowulf, daring and bold as ever but now weighed down with many years, raises his sword against the dragon and bring his defiance straight to its lair. Accompanied by his army of Geats and his right-hand man Wiglaf, he storms the dragon's lair and slays it at the cost, however, of his own life. It proved to be Beowulf's final battle. To Wiglaf's embarrassment, he witnessed how what were supposed to be fearless Geat warriors scamper and flee from the dragon. Only Wiglaf came to the aid of the single-minded Beowulf when he rushed and was mortally wounded by the mighty beast. After the terrific battle, only Wiglaf and a wounded dying Beowulf stood victorious. Beowulf confides to Wiglaf of his final requests: that a tower be built in his name at the edge of the sea and the dragon's treasure be buried beside it. Wiglaf lights Beowulf's funeral pyre, collects his ashes in the end and stores it in the tower that bears his name.

|

| Source: http://coolvibe.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/Warrior_Soul.jpg |

"Buliwyf, pale as the mist itself, garbed in white and bound in his wounds, stood erect upon the land of the kingdom of Rothgar. And on his shoulders sat two black ravens, one to each side; and at this sight the Northmen screamed of his coming, and they raised their weapons into the air and howled for the battle. Now Buliwyf never spoke, nor did he look to one side or another; nor did he give sign of recognition to any man but he walked with measured pace forward, beyond the line of the fortification, and there he awaited the onslaught of the wendol. The ravens flew off, and he gripped his sword Runding, and met the attack" (17).

Ibn Fadlan described Buliwyf in the way any Northman could conceive their chief Viking god Odin.

Despite the variations shared by the Beowulf story and the Ibn Fadlan report, it is easy to award the Beowulf story as one of the several offspring of Ibn Fadlan's work. However, such an appraisal will not go unchallenged. It is basically understood that before the version of the Beowulf story we know today was penned in the tenth century A.D. , an earlier composition of it was made two hundred years before, around the eighth century A.D. (18). The writer was believed to be an Anglo-Saxon poet and a Christian, and may have even been a monk. As far as the records go, this was the first time the Beowulf saga saw paper and ink. As far as the Beowulf tradition goes, however, experts believe that the epic had already been heavily circulating in Scandinavia as part of oral tradition over a hundred years before it hit Anglo-Saxon paper and ink! Estimates today favor the Beowulf story to have been composed in the sixth century A.D. after the death of the actual Hygelac, king of the Geats in 523 A.D., known in the legend to be Beowulf's lord and uncle (19). Hrothgar, the story's king of the Danes, is another character based on historical fact dated back to the sixth century A.D. and so is the inspiration for his famous mead hall, Hurot, discovered on recent 2013 excavations in Denmark (20).

Evidences, therefore, go as far as the sixth century. Around this period, Scandinavian denizens, mainly the Danes, were migrating over to Great Britain. It was a new land for Beowulf to conquer. But two hundred years later, a Christian monk in this new land turned the tables on Beowulf and infused the tale with Christian associations for its new Christianized audience, among whom were the very people who brought the epic into British shores. Another two hundred years later, around the time of Ibn Fadlan, a second edition of Beowulf was accomplished in the same Christian tradition as the first one. If the Ibn Fadlan report is not the second edition of the famous legend, would it have been possible that Ibn Fadlan was instead influenced by the Beowulf tale?

What we can be sure of is that Michael Crichton's novel Eaters of the Dead is an off-shoot of the Beowulf tale. In December 1992, Crichton wrote this statement in closing to the book's afterword: "When Eaters of the Dead was first published, this playful version of Beowulf received a rather irritable reception from reviewers, as if I had desecrated a monument. But Beowulf scholars all seem to enjoy it, and many have written to say so" (21).

LEFT: The death mask of Agamemnon (c.1550 to 1500 B.C.), discovered in Mycenae in 1876 by Heinrich Schliemann, the German archaeologist who discovered evidence of the Mycenean Civilization (1600 to 1100 B.C.) and the historic Trojan War (twelfth, thirteenth, or fourteenth centuries B.C.).

|

| © Heinz-Dieter Falkenstein/imageBROKER/Corbis |

As part of his recreation, Crichton had also designed his tale to be a first-hand account of an outsider since part of his objective was to reveal the factual core of the Beowulf legend. A narrative arranged in the form of a traveler's journal therefore conveyed the perfect mood for his details. And he knew just the guy to carry out this task: one factual Arab diplomat who lived in the tenth century A.D. and traveled into the mists of the North to live with the Russian Volgan Vikings known as the Rus. Crichton and Ibn Fadlan were old college buddies, if you know what I mean, and after many years, the first one got in contact with the latter by gathering the English-translated fragments of the Arab's report Crichton could find. From these, he formed the launch pad from where Ibn Fadlan would be hauled into a fantastic mission involving mist monsters and mighty masters of the deep uncharted eighth-century North.

The Vikings

|

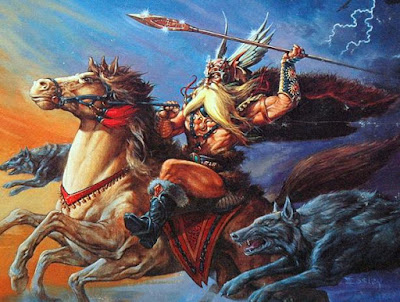

| ©2015 Frank Frazetta |

On page 65 of Eaters of the Dead, Ibn Fadlan took note that the term wyking came from the native word for "river" which is wyk.

The word Crichton chose to blur the distinction among all regional Vikings was the very generic "Northmen."

|

| ©2015 Frank Frazetta |

History now looks at the Viking invasions as among the most dangerous and destructive in Europe. they came in boats shaped like birds of prey, each carrying sixty warriors that quickly deploy and plunder and kill and leave a quickly as they came. These boats of both sail and oar stated from lands which could not support an extensive agriculture, so it was but natural for its inhabitants to taker to the sea and cultivate the watery resources. By the ninth century A.D., they were masters of the icy seas and of every river that led inland, and their boats proved instrumental in spreading the threat of invasion and piracy.

Yet also in the greater seas, they looked at vast distances in terms of opportunities rather than ominous horizons of sea monsters or the edge of the world, superstitious concepts that imprisoned the European brain of the Dark Ages. The Viking spirit led to the discovery of lands across the seas, like the Faroes, Iceland, Greenland, and Newfoundland in Canada.

|

| ©Corbis |

Wealth. For centuries, Northmen raids were bent on plundering wealth, and if there was one thing that could stop their devastation, it was wealth. The European nobles later knew this and so to save their kingdoms from further costly destruction, they resorted to a business-like arrangement that bought off the raiders and sent them off into other directions.

This policy worked so well for Europe that it actually caused economic recovery in the region as the destruction ground to a minimum. The Northman's adeptness for war, for instance, found its market with the Byzantine empire that frequently hired them as mercenaries and royal bodyguards. Because of their integration into main European affairs, a surprising talent of the Northman surfaced to finally bring the continent into a new age of economic recovery.

A scene from the animated movie The Secret of Kells (2009) depicting the horrors of the Northmen invasion. In the story, the wall a town worked so hard to build was not able to withstand the sudden attack of the Vikings.

Never had it been realized, even to us today, that the Vikings were outstanding government administrators. Probably the image of the berserking warrior had hidden the fact that there are lands that they claimed in the Mediterranean that rose to economic prominence because of the Northman's skill on bureaucratic affairs.

LEFT: Rollo Rognvaldsson, also known as "Rolf the Ganger" of Norway, "Marching Rolf" or "Rollo the Dane." Seized northern France in 911 A.D. and became its first duke. The territory which he wrested from Frankish king Charles the Simple became the best organized regions of France.

The Normans. Due to the lack of further resources to plunder, a Viking named Rollo (Hrolf) in 911 A.D. took possession of part of northern France and offered his allegiance to the Frankish king Charles the Simple in exchange to live peaceably on his kingdom. The king received Rollo and his descendants, and with the latter accepting Christianity, the state of Normandy was born: the first territory ever granted to the Northmen. After Normandy was granted its terms to exist, it quickly became one of the best organized parts of France. The Normans, as they were consequently called, used to their advantage institutions in the region which the Franks were not able to effectively use, when they were a part of Charlemagne's empire back in the eighth and ninth centuries. A century and a half later, in 1066, a young duke named William crossed the English Channel and in a single day conquered England, armed with nothing but a claim that he was promised the succession to the English throne. He was, of course, also accompanied by an infantry of 7,000 and a cavalry of 2.000. William, now called "the Conqueror," was crowned king of England on Christmas Day of that same year and placed his compact kingdom under absolute domination.

|

| ©Corbis |

During the eighty-eight years of Norman occupation, the rich spoke French while the poor spoke English. According to language historians, this is seen on how poultry and livestock names were retained in English use —like, "pig" (picg), "chicken" (cicen), "cow" (cu), "sheep" (sceap or scep), and "fish" (fisc)—while the delectable cuisine they became were given the French translations—like, "pork" (porc), "poulet" (as in bouillon de poulet for "chicken broth"), "beef" (buef), "mutton" (moton), "poisson" (as in de filets de poissons for "fish fillets"). The meal time terms also were transformed into French, words we use to this day like "lunch" and "dinner." Breakfast, however, was a meal given less importance in Europe during the Middle Ages and was even associated with the sin of gluttony in that it manifested the undisciplined drive of eating too soon. The French counterpart is déjeuneur, the meaning of which tended to shift towards "lunch." Like many "benevolent" conquerors in history, some matters which they believed were important to their subjects were left for the subjects to enjoy; and this is why "breakfast" made it to modern English while déjeuneur did not.

SOURCE: https://nicksirotich.files.wordpress.com/2012/01/mviking-web.jpg

The Normans allowed some aspects of the native English political system to exist, mainly to prop up their imported style of government; but in many ways, both contributed to each other's further development. And as it has become evident, the Vikings, who later became the Normans, adapted to and revolutionized the regions they have conquered by using the resources and institutions native in those very places.

Until William the Conqueror took possession of England, the nation had no standing army. Its soldiers were lent to the king by their lords in times of national crisis and then sent home when the threat had been averted. In fact, the king honored the sending-home part of the deal that it became severely difficult to keep the soldiers from returning home in times of special occasions, like harvest, as such was the situation when the invading William I landed on English shores. The victorious Norman duke, thereafter, declared himself absolute suzerain of the land and decreed that all knights and soldiers as his vassals, owing him military service.

It was not difficult for William I to restructure the English government at that time as it already possessed a form of feudalism as the one practiced in continental Europe. The country was already divided into "shires" (which later became counties), administered by the bishop, the earl, or the thane, and a shire-reeve, or sherrif, an appointee of the king to oversee the king's interest in the shire, like tax collection and presiding over the shire court in cases which came under his jurisdiction. All William I had to do was to position himself over all the thanes of the land, allow the thanes to keep their shires so long as they vowed allegiance to him, and grant the common lands to his Norman barons. Under his rule, the thanes and the Norman nobles became his direct vassals, vassals who had the right to let out the land again to subvassals who provided knight and military service (25).

William I carefully studied the elements of the English culture that he believed would help him function as absolute feudal lord as well as profitably enrich himself. As England learned feudalism from him, it was here where the Conqueror learned about the concept of the tenancy in socage in which a vassal was provided alternative ways to serve his master for land tenure other than military service. Examples of these were paying a fixed monetary amount, paying rent, or agricultural dividends. Serjeanty was another arrangement where the vassal became the king's armor-bearer, following his master to battle bearing the royal shield or suit of armor (26).

One other type was rare but was opened for the clergy since the Normans once obligated the Church to render military service for its estates. Soon, however, an arrangement was approved allowing service for priests or clergymen to say Masses, pray, give alms, or any service suited to their calling. It was called frankalmoign.

Sicilian Normans. As indicated earlier, the Normans, being Viking descendants, continued the tradition of utilizing the resources native to the lands they conquer to administer effectively and efficiently. It was no different when they captured the island of Sicily immediately after they ousted the Byzantine power from central and southern Italy. The year was 1071 and the power of the Muslim Empire was waning. The Normans, amazed at the eastern splendor of the Arabs offered cooperation with the island's former ministers to restore the grandeur of Sicily's layered culture. By 1130, the island became a culture jewel gathering scholars, scientists, artists, poets from every corner of the Mediterranean. Here, Arab Muslims, Jews, Byzantine Greeks, and Latin Normans flocked to form a single nation bound by toleration, justice, equality, and love of learning, giving Sicily the banner of the most civilized country in the western world. In prosperity it rivaled they Byzantine Empire that for centuries was hailed as the most powerful economy in Medieval Europe.

A noble-looking portrait of Robert de Hauteville, a.k.a. Guiscard, who was, in fact, once a bandit in Italy before he won the trust of the Pope in 1059 to protect the Holy See. In 1047, this impoverished Norman knight, seeking fortune, arrived at the Lombard-controlled region of central-southern Italy called Langobardia. His daring and cunning drew him the attention of Pope Nicholas II who invested him to be the Duke of Apulia and Calabria and become a nemesis to the Byzantine Empire. He led the attack on Sicily in 1061 and captured it ten years later, starting with the city of Messina and then on Palermo (27).

The Varangians and the Rus. Lastly, the very people whom Ibn Fadlan encountered were as bent on trade as they were on plunder. These were the eastern Vikings who plied the rivers of Russia and eastern Europe carrying their trade among the Slavs, the Byzantine Greeks, the Turks, and other Asiatic tribes that were pushing north-westward into Europe.

In the ninth century, the Vikings from Sweden sailed east, a logical direction for them to raid, where immediate settlements of Finns, Slavs, Russians, and other Baltic people were frequent victims plundered for their amber and fur. These goods were then taken down the great Russian rivers, the Volga especially, and traded with the Byzantine Greeks of Constantinople. During this period, the only hope of wealth was carving a trade path to Constantinople, an aspiration many businessmen have tried and failed because of the marauding activities of the Vikings, Magyars, and Muslims. But with the trading headed by the eastern Vikings, the enterprise along the Black and Caspian seas and up the Russian rivers vibrated with the promise of revenues as it attracted other cities along the route it plied.

ABOVE: The legendary Rurik who led his Varangian group to occupy Ladoga and later Novgorod. According to the Russian Primary Chronicle, compiled in 1113, Rurik entered Novgorod after its Slavic and other tribal population, which had previously ousted its former Nordic overlords, invited him and his group to restore law and order as no accord could be reached by the native leaders of the city.

It also attracted plunderers like Magyars, Avars, and Slavs to challenge aborning trade ventures in the regions above the Black Sea. In a determined resolve to enroot Viking interest in the region, these Scandinavians warrior-traders swore oaths to each other vowing mutual assistance and defense. It was a trust faithfully carried out among themselves by which they would be instantly known for: Varangians, where the Norse word war referred to an "oath sworn in fidelity," and thereby resulting to waering, or "one who has taken an oath of allegiance" (28).

As with their relatives who sailed west, these Varangians made their presence felt in the east with the same terror and ferocity than was unmistakably Viking. They carried their love for war, plunder, carnage, piracy, and business to Finland, the Baltic countries, Russia, and the Balkan domain above the Byzantine Empire. Part of these Varangian population established themselves in Russia and built the city of Novgorod in 850 A.D. also wresting Kiev from the Slavic tribes to later become the capital of a strong Viking state in Russia. By 859, they were exacting taxes from the Finnish and Slavic tribes and in 862 they take over the village of Staraya Ladoga in Russia from its Finnish and Slavic founders, later to become an important trading post in Eastern Europe. The Slavs, whose population outnumbered all other peoples in Eastern Europe, referred to the Nordic Kievan nobility as the Rus, distinguishing them above the common Varangian Viking who visited Kiev to trade, to offer loyalty and service as warrior, or hire a contingent of warrior Rus (29).

Rus etymological studies also have it that the word came from Ruotsi, the Finnish term for the Swedish country itself. The latter is derived allegedly from the Old Swedish rother, a maritime root word associated with rowing and ships that develops into rothskalar, meaning "rowers" or "seamen" (30).

By the ninth century, the Volga was an established trade route made possible by the Varangians. Through this channel, not only did Constantinople's wealth issue to and fro, but also conveyed the fierce reputation of both Varangian and Rus as formidable fighters. Constantinople did not just receive rumors from the north to know about this information as there were sporadic Varangian Rus attacks that attempted to crack Byzantine defenses as early as 860 up to 1043. In other words, while the Vikings were trading with them on one side, there was serious pounding on the other. There were even agreements between them wherein Kievan princes were given into marriage with Byzantine princesses. And this was one way Rus Varangians were introduced into the Byzantine Army as the elite contingent known as the Varangian Guard.

By associating themselves with the Byzantines, another legend emerged out of the Viking saga: The Varangians learned that the Eastern Roman Empire contracted foreign mercenaries ranging from Arabs to Lombards, Turks to Normans, Armenians to Hungarians, including tribes of the vast Slavic population. But it was not through this arrangement that would shape the mythical Varangian Guard. It was going to be out of the converging currents generated by the dilemmas separately experienced by Constantinople and Kiev during the tenth century.

In Kiev, a prince named Vladimir Sviatoslavich (ruled 980–1015) was forced to escape to Sweden when a usurping brother began executing his plan to seize the throne by taking down his contenders. With the help of a cousin, who was then no one else but the king of Norway, Vladimir returned to Kiev with a Viking army strong enough to take down a city—like Kiev—and get him on the seat of power. On his way, he captures and fortifies the cities of Polotsk and Smolensk through which he facilitates the recapture of the Rus capital and slays his murdering sibling. This is where the trouble begins. After all the excitement and the screams of battle, Vladimir's Viking kin, the ones he and his cousin rallied into a ship that left Sweden to stage a coup d'etat, well, they were expecting their money—which the new king, Vladimir the Great, still had none to give. Imagine the look on their faces as they gazed at the new landscape, dreaming of a new life in this strange new land, and suddenly hearing that the prince they installed needed more time to come up with the promise. The time he actually took amounted to ten years. We could only imagine the pain in his ass with the trouble stirred in his kingdom by a great number of unpaid plunderers!

Yet out of these Swedes was born the first generation of the Byzantine Varangian Guard that served as the Imperial bodyguard and elite fighting regiment of the Byzantine army (Frank Westenfelder, "The Varangian Guard: The Vikings in Byzantium). These warriors were handsomely compensated and greatly honored. In times of battle, there were only sent out at the most critical situations when only at these instances was the wonder and terror worked to turn the tide into Byzantine's favor. It was reported that the Varangians, in the thick of battle, underwent a trance-like rampage that seemed to make them impervious to pain, as if the deepest gashes of wounds or massive loss of blood meant for nothing. It was, of course, a description of the Viking berserker's rage.

The Varangians proved to be fiercely loyal, but only to the office of emperor and not to the individual who dons the title. On another matter, not only were they awesome in the battlefield, their brutality was unspeakable. In one account, Varangians were described to have chased down a fleeing army and then hacked them to pieces with glee. During times of peace, they were known to function as keepers of the peace in the empire. And in times of the Emperor's death, they were allowed ransack his treasury and carry away as much as they could.

Icelandic Northmen. Far to the north, there were Vikings who found no need to descend to warmer waters. Frigid though was the climate these Northmen continued to endure, their lives were ignited with the fire of letters and religion that around the period of the eleventh to the fourteenth centuries was penned the greatest of all Viking literatures: the Edda.

For the first time, there was a chance for the non-Northman to look into the mind of the Viking, why he feared no death, why he looked at war the way he did, how he viewed death and the hereafter, and how much death was a part of the Northman culture. The books of the Edda were accomplished around the time when the Christian Church managed European politics. It was as if a reminder for ages to come of a culture on its way out as its children were embracing the way of the Cross and proving to be its faithful followers.

From plunderers to nation-builders, from pillagers to faithful confidants, we can see how the Vikings changed Europe for bad and for good; we have also seen how Europe changed them. In time, many of them embraced Christianity and were assimilated into the countries they conquered, seeing that they reasonably adapted to the resources available in the regions they occupied. END.

Endnotes:

(1) Michael Crichton, Eaters of the Dead (Ballantine Books: New York, 1991). p.35.

(2) Ibid. p.33.

(3) Ibid., p,31.

(4) Ibid., pp.54–55.

(5) Ibid., p.54.

(6) Ibid., p.1.

(7) Ibid., p.2.

(8) Ibid., p.121.

(9) Ibid., p.60.

(10) Ibid., p.164.

(11) Ibid., p.157.

(12) Ibid., p.158.

(13) Ibid., p.163.

(14) Ibid., p.121.

(15) Ibid., p.165.

(16) Ibid., p.33.

(17) Ibid., p.164.

(18) Beowulf (http://www.sparknotes.com/lit/beowulf/context.html), ©2015 SparkNotes LLC, All Rights Reserved.

(19) Jan Purnis, Historical Legend in Beowulf, Copyright ©2000 .(http://homes.chass.utoronto.ca/~cpercy/courses/1001Purnis.htm)

(20) Hugo Gye, "Secrets of Beowulf Revealed: Relics discovered at Danish feasting hall which featured in Britain's oldest epic poem" MailOnline News, 26 August 2013 (http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2402079/Secrets-Beowulf-revealed-Relics-discovered-Danish-feasting-hall-featured-Britains-oldest-epic-poem.html).

(21) Eaters of the Dead, p.80.

(22) Ibid., p.52.

(23) Old English Core Vocabulary, http://www.st-andrews.ac.uk/~cr30/vocabulary/

(24) Your Dictionary, Copyright © 1996-2015 LoveToKnow, Corp., http://reference.yourdictionary.com/dictionaries/old-english-words-and-modern-meanings.html.

(25) Stewart C. Easton, The Heritage of the Past: From the Earliest Times to the Close of the Middle Ages (Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, December 1961) page 717.

(26) Ibid., p.720.

(27) http://interamericaninstitute.org/norman_sicily.htm

(28) Arkadii Zhukovsky, Varangians, Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (http://www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/display.asp?linkpath=pages%5CV%5CA%5CVarangians.htm), ©2001 All Rights Reserved. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies.)

(29) Frank Westenfelder, "The Varangian Guard: The Vikings in Byzantium," Soldiers of Misfortune: The History of Merenaries (http://www.soldiers-of-misfortune.com/history/varangian-guard.htm). Copyright 2011.

(30) Christie Ward/Gunnvôr silfrahárr, "Vikings in the East: Rus and Varangians," The Viking Answer Lady (http://www.vikinganswerlady.com/varangians.shtml), Updated 6/13/2015. Copyright 2015.

Additional Reference:

Online Etymology Dictionary (http://www.etymonline.com), Copyright ©2001-2015 Douglas Harper.